The use of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio to predict complications post cardiac surgery

IntroductionOther Section

Cardiac surgery, such as coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), and valve repair and replacement, remains the gold standard treatment for severe coronary artery disease and valvular heart disease. With improving results, surgeons in this era are not only trying to improve mortality rates, but morbidity rates as well.

Cardiac surgery induces an acute systemic inflammatory response due to cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), myocardial arrest, and surgical trauma. There is increasing evidence that increased inflammation leads to an increased risk of complications postoperatively (1), such as atrial fibrillation (AF) and acute kidney injury (AKI). The causes of AF and AKI post cardiac surgery are multifactorial and are yet to be fully understood (2).

AF is the most common arrhythmia following cardiac surgery, with reported incidences of 30–40% post CABG, 50% post valve surgery, and up to 64% after combined procedures (3,4). Postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) is associated with increased risk of stroke, heart failure, prolonged inpatient hospitalisation, and increased costs (2,3). Acute kidney injury occurs in up to 30% of patients post cardiac surgery, with 1–2% requiring renal replacement therapy (5). AKI post cardiac surgery is associated with an increased risk of mortality up to 10 years postoperatively, independent of other risk factors, even in patients whose renal parameters returned to baseline levels (6). The ability to predict and prevent these complications is therefore important in reducing patient morbidity and optimising use of healthcare resources.

NLR has been shown to be a useful marker of inflammation. Evidence in the literature suggests that NLR can be used to predict AF (7), AKI (8), prolonged length of stay, poorer outcomes (9), and mortality (10,11) post cardiac procedures. However, this had not been demonstrated consistently (12).

This aim of this study was to expand the understanding of the relationship between inflammation and the development of complications post cardiac surgery.

MethodsOther Section

A retrospective review of patients who underwent a cardiac procedure involving first-time sternotomy for on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting or valve repair/replacement for primary valve pathology over a 5-year period until September 2016 was performed. Patients were excluded if they were under 18 years of age, if their procedure did not involve cardiopulmonary bypass, if their valve disease was due to infective endocarditis, if they had previous median sternotomy, or if they died within 48 hours of surgery.

The database was created using the prospectively maintained theatre logbooks and electronic patient records of inpatient hospital stay, operative details, and relevant blood results. Baseline neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and postoperative NLR on day 1 and day 2 were collected. All preoperative analyses used the most recent full blood count (FBC) and urea and electrolyte (U&E) samples obtained before surgery. Postoperative FBC samples obtained on postoperative days 1 and 2 were used to record neutrophil and lymphocyte levels. U&E samples were analysed for 7 days postoperatively, for change in serum creatinine as compared with the most recent preoperative U&E, to assess for AKI. Analysis controlled for known risk factors for complications including patient age, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, previous history of AF, preoperative chronic kidney disease (CKD), and higher EuroSCORE II. Longer CPB and cross clamp time may lead to increased inflammation, and were included in analytical models. Missing data was excluded from analysis.

Occurrence of POAF and AKI within 7 days or duration of hospital stay were recorded. POAF was defined as occurrence of an irregular rhythm in the absence of identifiable P-waves lasting more than 30 seconds on continuous telemetry monitoring, or demonstrated on 12-lead electrocardiogram. AKI was defined as per Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. Urine output criteria were not used in this study due to the multifactorial causes of the variation in urine output post cardiac surgery other than AKI.

A simplified sample size calculation was performed using OpenEpi sample size for comparing two means calculator with a 95% confidence interval, 80% power, and predicted group size ratio of 1.25 and mean and standard deviations of each group calculated from initial data. Necessary sample size to show a significant difference in NLR, where P<0.05, between groups was 726.

Ethical Approval was granted by the hospital ethics approval committee for this retrospective study.

Statistical analysis was performed using StataCorp. 2015. (Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.) Descriptive analyses were provided using mean and standard deviation for continuous data, and absolute values and percentages for categorical data. Univariate logistic regression was performed. Backward stepwise multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify independent predictors of POAF and AKI. Separate models were constructed to look at preoperative NLR, day 1 NLR, and day 2 NLR. Subgroup analysis of patients who underwent CABG alone was performed in the same manner. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsOther Section

There were 1,010 cardiac procedures involving CABG or valve repair/replacement for primary valve pathology in our unit between September 2011 and September 2016 for whom full records were available. One hundred and four patients were excluded from analysis: 23 as their operation was performed without CPB, 43 patients as they had previous median sternotomy, 30 patients as their valvular disease was due to infective endocarditis, 6 patients as they died within 48 hours of surgery, 1 patient as she was less than 18 years old, and 1 patient because no record was available.

Nine hundred and six patients were included for analysis. Seven hundred and four patients (77.7%) were male. Mean age was 66.8 years (SD 9.97), 489 patients (54.0%) had hypertension, 209 patients (23.1%) had diabetes mellitus, 58 patients (6.4%) had COPD, 92 patients (10.2%) had pre-existing atrial fibrillation, and 48 patients (5.3%) had chronic kidney disease. Mean EuroSCORE II was 2.74 (SD 3.85). Mean CPB time was 116.46 minutes (SD 37.86), mean cross-clamp time was 84.7 minutes (SD 30.49).

Postoperative AF

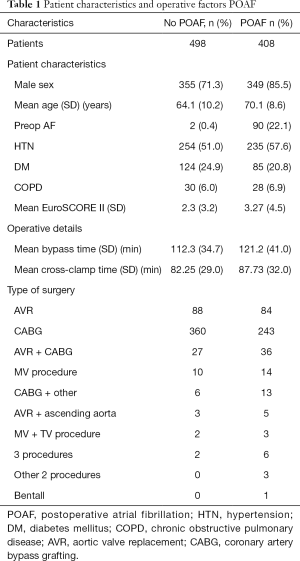

Of the 906 patients included for analysis, 498 (54.97%) remained in sinus rhythm for the duration of their inpatient stay, and 408 patients (45.03%) developed POAF. Demographics, comorbidities, and operative details are described in Table 1.

Full table

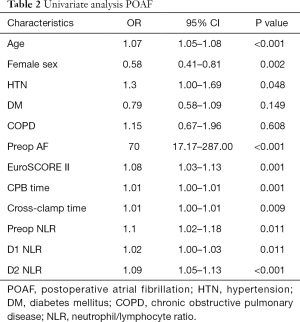

Results of univariate analysis for factors associated with POAF are shown in Table 2. Older age, male gender, hypertension, pre-existing atrial fibrillation, higher EuroSCORE II, longer CPB and cross-clamp times, higher preoperative NLR, day 1 NLR, and day 2 NLR were significantly associated with postoperative atrial fibrillation.

Full table

Pearson’s correlation showed that CPB time and cross-clamp time were strongly correlated (r=0.91). Cross-clamp time was excluded from further models. Preoperative NLR, day 1 NLR, and day 2 NLR were weakly correlated. Separate models for multivariate analysis were constructed for each.

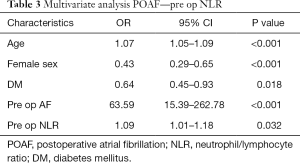

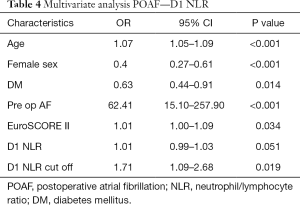

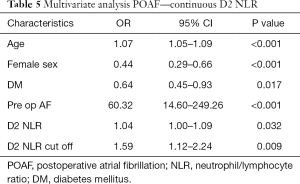

Results of backward stepwise regression analysis for factors associated with POAF in all patients are shown in Tables 3-5. Older age and preoperative AF remained significantly associated with POAF in all multivariate analysis models which include all patients. Higher EuroSCORE II was significantly associated with POAF in multivariate analysis models for day 1 NLR. Female gender and diabetes mellitus were protective for POAF in all multivariate analysis models.

Full table

Full table

Full table

Preoperative NLR was significantly associated with POAF (OR 1.09, P=0.032).

Postoperative day 1 NLR was borderline significantly associated with POAF as a continuous variable (OR 1.01, P=0.051), but was significantly associated with POAF as a dichotomous categorical variable around a cut off of 26.25 (OR 1.71, P=0.019).

Postoperative day 2 NLR was significantly associated with POAF both as a continuous variable (OR 1.04, P=0.032) and a dichotomous categorical variable around a cut off of 10 (OR 1.59, P=0.009).

Receiver operating characteristic curves explored the relation between NLR and POAF. Using a cut off point of 8, preoperative NLR predicted POAF with a sensitivity of 6.2% and a specificity of 98.87%. Using a cut off point of 26.25, postoperative day 1 NLR predicted POAF with a sensitivity of 15.76% and a specificity of 90.71%. Using a cut off point of 10, day 2 NLR predicted POAF with a sensitivity of 33.33% and a specificity of 80.49%.

AKI

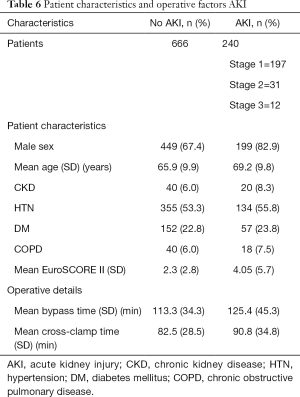

Of the 906 patients included for analysis, 666 patients (73.5%) did not develop an AKI, and 240 patients (26.5%) developed an AKI. Of these 240 patients, 197 were stage 1, 31 were stage 2, and 12 were stage 3, as defined by the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. Demographics, comorbidities, and operative details are described in Table 6.

Full table

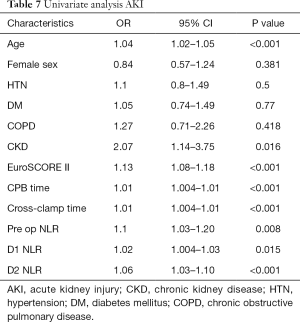

Results of univariate analysis for factors associated with AKI in all patients are shown in Table 7. Older age, chronic kidney disease, higher EuroSCORE II, longer CPB and cross-clamp times, higher preoperative NLR, day 1 NLR, and day 2 NLR were significantly associated with postoperative AKI.

Full table

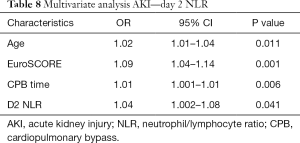

Backward stepwise multivariate regression analysis was performed for factors associated with postoperative AKI in all patients. Cross-clamp time was not included in the model as it was highly correlated with CPB time. Most episodes of AKI occurred on day 1 or day 2 postoperatively, and so day 1 NLR and day 2 NLR were not thought to be clinically relevant in predicting AKI. However, models were constructed for day 1 and day 2 NLR to assess whether there is an association with postoperative AKI, and therefore if inflammation plays a role in its development. Preoperative NLR was not significantly associated with AKI in multivariate analysis (P=0.283). Older age, higher EuroSCORE II, and longer CPB time were independently significantly associated with AKI post cardiac surgery. Day 1 NLR showed a trend towards association with postoperative AKI on multivariate analysis (P=0.099). Day 2 NLR is significantly associated with postoperative AKI (P=0.041) (Table 8).

Full table

Subgroup analysis of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting and POAF

There were 601 patients who underwent first time on-pump isolated coronary artery bypass grafting in the study period. Three hundred fifty-eight patients (59.6%) remained in sinus rhythm postoperatively. Two hundred forty-three patients (40.4%) developed AF postoperatively within their inpatient stay. Older patient age, preoperative AF, higher EuroSCORE II, and higher pre- and postoperative NLR were associated with increased likelihood of developing POAF in univariate analysis. Female gender and diabetes mellitus were protective.

Age, preoperative AF, and higher EuroSCORE II were independently significantly associated with postoperative AF in backward stepwise multivariate analysis in the CABG cohort. Female gender and diabetes mellitus remained significantly protective. Preoperative NLR and day 2 NLR were not significantly associated with POAF. Postoperative day 1 NLR was not significantly associated with POAF as a continuous variable (P=0.177), but was significantly associated with POAF as a dichotomous categorical variable around a cut off of 26.25 (OR 1.86, P=0.045).

DiscussionOther Section

Cardiac surgery is the gold standard treatment for many patients with coronary artery disease and valvular heart diseases. In this era of low mortality rates, surgeons are now striving to improve morbidity. It has been shown that increased inflammation from patient factors, choice of anaesthetic, degree of surgical trauma, degree of myocardial ischaemia, and duration of cardiopulmonary bypass can lead to complications, such as atrial fibrillation and acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Studies have shown that patients who develop POAF may have increased acute oxidative stress compared with matched patients who remain in sinus rhythm after cardiac surgery (13), suggesting an individual susceptibility to develop complications related to inflammation. The phenomenon of increased inflammation associated with cardiopulmonary bypass is well established. CPB activates contact systems of plasma proteins, intrinsic coagulation, extrinsic coagulation, complement, and fibrinolytic pathways, as well as activating platelets, neutrophils, monocytes, endothelial cells, and lymphocytes (14). Thrombin and other coagulation components and their products have proinflammatory effects. Thrombin also has direct chemotactic activity for neutrophils (15).

Total white blood cell count (WCC), neutrophil count, lymphocyte count have been used to predict cardiovascular outcomes, but individually are limited by their complex, non-linear link with outcomes, and confounding relationships with other variables (10). Leukocyte subtypes and ratios between them have been shown to be more useful in predicting outcomes for cardiovascular procedures. Elevated neutrophils represent activated non-specific inflammation. Decreased lymphocytes are associated with poorer general health, increased physiological stress, and depressed immune response. NLR integrates these two opposite immune pathways (16).

Postoperative AF

This study showed that neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio can be used to predict complications post cardiac surgery. Higher preoperative NLR was significantly associated with postoperative atrial fibrillation (OR 1.09, P=0.032). Postoperative day 1 and day 2 NLR predicted postoperative atrial fibrillation in analyses including all patients. Postoperative day 1 NLR showed a trend towards association with POAF as a continuous variable but did not reach significance (OR 1.01, P=0.051). Day 1 NLR above a cut off of 26.25 predicted POAF (OR 1.71, P=0.019). Postoperative day 2 NLR was significantly associated with POAF both as a continuous variable (OR 1.04, P=0.032) and a dichotomous categorical variable around a cut off of 10 (OR 1.59, P=0.009). This is in keeping with the theory that a patient’s increased inflammatory response contributes to POAF. Individually, it is well recognized that several factors such as race, gender and disease states contribute to variation in the mounting of inflammatory response upon stimulation (17-19). The use of cut off points allows for patients to be stratified into high and low risk groups for developing postoperative atrial fibrillation. This can translate to clinical practice by allowing for the selection of patients at high risk for prophylactic treatment. Older age, male gender, preexisting atrial arrhythmias, and higher EuroSCORE II were also associated were POAF, in keeping with previous literature. Diabetes mellitus was protective for postoperative arrhythmias in this cohort of patients in this study, which is at odds with previous research (20), although this has not been shown consistently (21). In our institution, we perform a rigorous investigation and treatment for diabetes mellitus starting from the preassessment stage all through to postoperative care. Therefore, this may have had a protective effect on lower inflammation and hence lower rates of POAF.

Subgroup analysis was performed of patients undergoing CABG. Day 1 NLR as a categorical variable remained significantly associated with POAF. Preoperative NLR was not shown to be predictive of POAF either as a continuous or categorical variable. However, the trend towards significance would suggest that this warrants further study. Postoperative day 2 NLR was not significantly associated with POAF.

A 2010 study by Gibson et al. looked at 275 patients undergoing CABG in their institution over a 21-month period (7). They also excluded patients undergoing emergency surgery, but unlike our study, included patients undergoing off-pump surgery, and excluded patients with prior atrial arrhythmia. Patient demographics were similar to those in the CABG subgroup analysis of this study. A study by Durukan et al. in 2014 assessed 523 patients over an 18-month period undergoing elective on-pump CABG in their institution. The Durukan et al. study also assessed preoperative NLR and day 2 NLR. 17.4% of patients developed POAF in their study, much lower than the number of patients in both the Gibson study, and the present study. It is likely that the rate of POAF is slightly higher in this study due to the inclusion of patients with prior arrhythmias. Durukan et al. did not find any significant association between NLR and POAF. The Gibson et al. study looked at preoperative NLR and day 2 NLR, as well as other leukocyte values and CRP. They found that preoperative NLR was not associated with POAF as a continuous variable, but that is was significantly associated with POAF as a dichotomous variable around a cut off of 2.63. Day 2 NLR was significantly associated with POAF as both a continuous variable and categorical variable around a cut off of 10.14 in their study. This finding was not replicated in this study, which found that the only NLR variable to remain significantly associated with POAF in the CABG subgroup analysis was day 1 NLR as a dichotomous variable around a cut off of 26.25. This may be due to greater accuracy with a larger sample group in this study, or the difference in inclusion and exclusion criteria leading to different patient cohorts, particularly this study’s inclusion of patients with prior arrhythmias, which had the strongest association with POAF across all analyses (OR 59.9–70.34). It is known that off-pump CABG is associated with lower inflammatory response and lower rates of POAF (22). Therefore, in this study, we only included on-pump surgery to standardise the NLR. This may also explain the disparity in results.

Various strategies have been employed in an effort to prevent postoperative atrial fibrillation. A 2013 Cochrane review concluded that pharmacological interventions such as the use of betablockers, amiodarone, sotalol, and magnesium significantly reduced the incidence of POAF as well as non-pharmacological interventions such as atrial pacing and posterior pericardiotomy (23). Other studies demonstrate that potassium supplementation and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (24), and pre-treatment with statins may reduce the rate of POAF (25). Overall, prophylactic treatment of atrial fibrillation has been shown to reduce the incidence of stroke, decrease the length of stay, and reduce cost of inpatient episodes. However, prophylaxis of AF does not have a significant impact on postoperative all cause mortality or cardiovascular mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery (23). These treatments all have significant side effects. This study allows for selection of patients who are most likely to have POAF and therefore most likely to benefit from prophylactic measures, leading to a reduction in overtreatment, side-effects, and cost. Further research of prophylaxis of POAF in selected high-risk patients is necessary.

Postoperative AKI

Preoperative NLR was not significantly associated with AKI in this study (P=0.283). Although the majority of AKIs occur in the first postoperative days, and therefore day 1 and day 2 NLR would not be clinically useful in predicting AKI, they were included in the analysis to assess whether higher NLR was associated with increased risk of developing AKI, and suggest a link between inflammation and AKI. Day 1 NLR showed a trend towards association and day 2 NLR was significantly associated with AKI (P=0.041). This strengthens the evidence that increased inflammation plays a role in the development of AKI. In keeping with the literature, older age, higher EuroSCORE II, and longer CPB time were independently significantly associated with AKI post cardiac surgery in multivariate analysis.

A 2015 study by Kim et al. to assess the association between NLR and AKI post cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass included 590 patients where 28.1% developed AKI in the first 7 postoperative days (8). This was slightly higher than 26.5% in the current study. Similar to the current study, the study by Kim et al. demonstrated that preoperative NLR did not predict postoperative AKI. They found that immediate postoperative, and day 1 NLR were significant predictors of AKI. In the current study, the association between day 1 NLR and AKI was not significant. However, the present study examined day 2 NLR and found a significant link between raised day 2 NLR and AKI. From their data, 41.2% of patients had CPB times longer than 180 minutes, compared to just 7% of operations in the present cohort. This may have led to greater levels of inflammation in their patients, and larger differences which were easier to detect.

This study has the advantage over previous similar studies of having wider inclusion criteria, which makes the results more applicable to clinical practice. It also includes a larger patient cohort, adding power to the results over previous studies. This study has limitations inherent to a retrospective design. The exclusion of patients who had redo-operations, infective endocarditis, and procedures for primary aortic pathology means this data cannot be used to draw conclusions in these groups of patients. The study is limited by the use of continuous telemetry and 12-lead ECG for the diagnosis of POAF. As these modalities are user-dependent, it is possible that short episodes of atrial fibrillation were not recorded in this study.

ConclusionsOther Section

Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is associated with atrial fibrillation post cardiac surgery. Specific cut offs can be used to categorise patients as high or low risk of developing POAF. Preoperative NLR was not associated with postoperative acute kidney injury in this cohort, but association of postoperative NLR parameters suggests a role for increased inflammation in the pathophysiological mechanism of AKI after on-pump cardiac surgery.

AcknowledgmentsOther Section

RC Weedle would like to thank Prof Tom Fahey for his guidance with planning the design of this study, and Fiona Boland for her help with statistical analysis.

FootnoteOther Section

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Ethical Approval was granted by the hospital ethics approval committee for this retrospective study.

ReferencesOther Section

- Anselmi A, Possati G, Gaudino M. Postoperative inflammatory reaction and atrial fibrillation: simple correlation or causation? Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:326-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lomivorotov VV, Efremov SM, Pokushalov EA, et al. New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation After Cardiac Surgery: Pathophysiology, Prophylaxis, and Treatment. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2016;30:200-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rho RW. The management of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Heart 2009;95:422-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maisel WH, Rawn JD, Stevenson WG. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:1061-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huen SC, Parikh CR. Predicting acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a systematic review. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:337-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hobson CE, Yavas S, Segal MS, et al. Acute kidney injury is associated with increased long-term mortality after cardiothoracic surgery. Circulation 2009;119:2444-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gibson PH, Cuthbertson BH, Croal BL, et al. Usefulness of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio as predictor of new-onset atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol 2010;105:186-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim WH, Park JY, Ok SH, et al. Association Between the Neutrophil/Lymphocyte Ratio and Acute Kidney Injury After Cardiovascular Surgery: A Retrospective Observational Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1867. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giakoumidakis K, Fotos NV, Patelarou A, et al. Perioperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of poor cardiac surgery patient outcomes. Pragmat Obs Res 2017;8:9-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gibson PH, Croal BL, Cuthbertson BH, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and outcome from coronary artery bypass grafting. Am Heart J 2007;154:995-1002. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sinan Guvenc T, Ekmekci A, Uluganyan M, et al. Prognostic Value of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio for Patients Undergoing Heart Valve Replacement. J Heart Valve Dis 2016;25:389-96. [PubMed]

- Durukan AB, Gurbuz HA, Unal EU, et al. Role of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in assessing the risk of postoperative atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2014;55:287-93. [PubMed]

- Ramlawi B, Otu H, Mieno S, et al. Oxidative stress and atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a case-control study. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84:1166-72; discussion 1172-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edmunds LH Jr. Inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:S12-6; discussion S25-8.

- Levy JH, Tanaka KA. Inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:S715-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shao Q, Chen K, Rha SW, et al. Usefulness of Neutrophil/Lymphocyte Ratio as a Predictor of Atrial Fibrillation: A Meta-analysis. Arch Med Res 2015;46:199-206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferguson JF, Patel PN, Shah RY, et al. Race and gender variation in response to evoked inflammation. J Transl Med 2013;11:63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laurson KR, McCann DA, Senchina DS. Age, sex, and ethnicity may modify the influence of obesity on inflammation. J Investig Med 2011;59:27-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, et al. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med 1997;336:973-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Movahed MR, Hashemzadeh M, Jamal MM. Diabetes mellitus is a strong, independent risk for atrial fibrillation and flutter in addition to other cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol 2005;105:315-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tadic M, Cuspidi C. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation: From mechanisms to clinical practice. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2015;108:269-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dieberg G, Smart NA, King N. On- vs. off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2016;223:201-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arsenault KA, Yusuf AM, Crystal E, et al. Interventions for preventing post-operative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing heart surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013.CD003611. [PubMed]

- Mathew JP, Fontes ML, Tudor IC, et al. A multicenter risk index for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. JAMA 2004;291:1720-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patti G, Bennett R, Seshasai SR, et al. Statin pretreatment and risk of in-hospital atrial fibrillation among patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a collaborative meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials. Europace 2015;17:855-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]