Primary melanoma of the testis: myth

We read with interest the results of the retrospective study by Hadjinicolaou et al. (1) which described a case of primary small bowel malignant melanoma (SBM) in a 60-year-old man with review of the literature. The authors conclude that primary SBM is a rare entity, affect more frequently the men, with debatable pathophysiology.

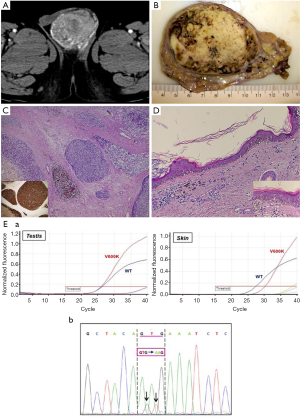

We would like to express some observations that can clarify the validity of their conclusions. Interestingly, we observed a case of malignant melanoma in the testis. Testicular metastases are usually observed in patients with a history of cancer, although in up to 10% of cases a palpable testicular mass may be the first manifestation of an occult neoplasm (2). Mean patients age is 60 years (range, 19–90 years) and most of these tumors are unilateral. Melanoma metastases occur in 5.7% of cases and are very rarely diagnosed in living patients. When it is the first manifestation of the disease, it is frequently very difficult to identify primary skin melanoma that poses a diagnostic challenge for clinicians. On the basis of mesodermal testis histogenesis, Katiyar et al. (3) hypothesised the theoretical presence of melanocytes even in the testis, then the development of a primary melanoma of the testis. The question is: does non-skin melanoma exist? This is currently a hot topic in literature, especially in gastrointestinal melanoma, yielding many theories but no universally accepted interpretation. We report a hypertensive 60-year-old male hospitalized for pontine hemorrhage with IV ventricle flood. Abdominal examination revealed a right testicular mass, inhomogeneous and hypervascular at CT-scan (Figure 1A). Multiple abdominal lymphadenopathies and bilateral adrenal gland nodules were detected. Right orchiectomy was performed. Gross examination revealed a testis weighing 100 gr and measuring 7.5 cm × 6 cm × 5.8 cm, filled with a greyish nodular mass with black punctae (Figure 1B). Histology showed epithelioid and spindle cells with high-grade atypia, a high mitotic index, diffuse vascular invasion, necrosis and focal pigment deposits (Figure 1C). The residual seminiferous tubules were atrophic. Immunohistochemistry showed intense expression of Melan-A (MART1), Melanoma-Ag (HMB45), S100-protein and vimentin. Melanoma of the testis was diagnosed (primary or secondary?). Patient’s history was unremarkable. Postoperative dermatological consultancy demonstrated a pigmented dysplastic lesion, 6 mm in diameter, at the left clavicle, subsequently removed. No homolateral axillary lymphadenopathies were detected, nor were melanocytic lesions of the penis or urethral meatus observed. Microscopically, a junctional proliferation of atypical melanocytes with a lymphocytic infiltrate of superficial derma was observed and a “cutaneous melanoma with extensive regression area” was diagnosed (Figure 1D). Mutational analysis of the BRAF gene by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed in both skin and testicular samples. Tumor specimens were screened for hot-spot mutations in codon 600 of the BRAF gene. Genomic DNA was isolated from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues containing at least 70% of neoplastic cells. Activating mutations in codon 600 of BRAF were identified through RT-PCR and each mutation was confirmed by direct Sanger sequencing. Both samples harbored a GTG to AAG (c.1798_1799delinsAA) dinucleotide mutation of BRAF replacing the encoded amino acid Valine by Lysine (V600K) (Figure 1E). BRAF V600K mutations have poor long-term prognosis (4). In this analysis we demonstrate that the testis tumor was secondary to a regressed cutaneous melanoma and that metastases may take several routes (i.e., retrograde venous extension, arterial embolism, retrograde lymphatic extension etc.).

So, when a non-skin melanoma is diagnosed, a close examination of the skin should be performed because a regressed melanoma should be always excluded. Moreover in term of prognosis the BRAF-mutational analysis is recommended to explaining the response to therapy. Future research should focus on finding additional parameters (i.e., molecular) that might distinguish the skin melanomas from non-skin melanomas or detected the melanoma molecular subtype with a higher metastatic potential. Therefore, the molecular profile, in the absence of an evident cutaneous melanoma, represents a crucial milestone not only in the understanding of non-skin melanoma’s pathogenesis, but to detect the genes that are important for a personalized therapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Mary V. Pragnell, BA, for language assistance.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Consent for data publication was obtained from a relative of the patient.

References

- Hadjinicolaou AV, Hadjittofi C, Athanasopoulos PG, et al. Primary small bowel melanomas: fact or myth? Ann Transl Med 2016;4:113. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. Eds Moch H, Humphrey PA, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. Lyon, 2016.

- Katiyar RK, Singh A, Kumar D. Primary melanoma of testis. J Cancer Res Ther 2008;4:97-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sahadudheen K, Islam MR, Iddawela M. Long Term Survival and Continued Complete Response of Vemurafenib in a Metastatic Melanoma Patient with BRAF V600K Mutation. Case Rep Oncol Med 2016;2016:2672671. [PubMed]