Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a case report and literature review

Introduction

Among malignant tumors, lung cancer poses one of the greatest threats to human health and life. A survey conducted by the Cancer Registration Office of the National Cancer Center in 2019 revealed that in 2015, there were approximately 877,000 new cases of lung cancer in China, with an incidence rate of 57.26 per 100,000 (1). More than half of lung cancer patients are older than 65 years old, and these patients have a higher mortality rate than younger patients (2). According to different stages, there are many new methods for the treatment of elderly patients with lung cancer. For patients with early stage lung cancer, minimally invasive surgery is often used. At the same time, in order to further reduce the impact on the respiratory system, intentional segmentectomy or Partial wedge resection were performed. For locally advanced and advanced patients, as a whole for chemotherapy, multiple clinical trials conducted in the elderly have shown that platinum-based dual-drug combination therapy has achieved satisfactory results. TKI targeted therapy drugs are carrying specific drivers. Elderly patients with gene mutations show good response and tolerance, but specific gene mutations occur at a significantly low frequency in elderly patients. Lung cancer ranks first in terms of mortality rate among all cancer types in China and its prevention and control are of great importance. The prognosis of lung cancer patients is closely related to its stage at the time of initial diagnosis. From stage IA to stage IIIB, the 5-year survival rate decreases from 90% to 24% (3). Most patients require adjuvant chemotherapy, but this only increases the 5-year survival rate by 4–5% (4,5). Therefore, a more effective treatment is urgently needed.

Fortunately, the emergence of immune checkpoint blockade therapy has greatly improved the treatment of solid tumors, including lung cancer. After its application in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the 5-year overall survival (OS) of all patients reached an astonishing 23.2%, and among patients with a high expression of PD-L1 reached 29.6% (6). The positive therapeutic effect of immunotherapy in unresectable lung cancer has triggered great interest in exploring its potential role in resectable NSCLC. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for patients with NSCLC was first reported by Patrick Forde at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) conference in 2016 (7). Since then, several kinds of clinical studies have been continuously conducted, with the first being Checkmate 159 and the most recent being Keynote 671. The latest results from the Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and nivolumab in resectable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) study showed a major pathological response (MPR) rate of 83%, a pathological complete response (pCR) rate of 71%, and 38 patients (93%) showing downstaging after neoadjuvant therapy (8). The results also indicated that neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy was the best treatment mode. As promising as these results are, their application to elderly patients is limited as they are rarely included in clinical trials. This may be because immunotherapy is considered to have a poor therapeutic effect in elderly patients for several reasons. In comparison to those younger, the elderly generally show decreased clearance due to the age-related decline in kidney quality, and the change in glomerular filtration rate affects the clearance of anticancer drugs (9). Decreased liver blood flow and first-pass metabolism in the liver can also change the pharmacokinetics of anticancer drugs. Another factor is immunosenescence, which refers to immune disorders resulting from pro-inflammatory characteristics due to the imbalance between inflammation and anti-inflammatory mechanisms seen with age (10-12). We report on an elderly patient who received neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy for the treatment of lung cancer. The results showed an obviously shrunken focus and good postoperative recovery. This paper presents a case report and review of the relevant literature to expand upon clinical treatment data.

We present the following article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-7767).

Case presentation

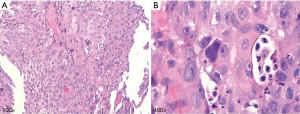

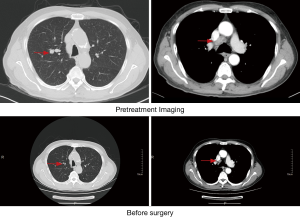

A 76-year-old male presented with a chief complaint of cough and sputum for more than 6 months beginning in July 2019, accompanied by blood-stained sputum for 2 weeks. He had a long history of smoking 20 cigarettes each day for more than 40 years but had quit 6 years previous. He denied a family history of tumors and was otherwise healthy with no signs of disease or obvious abnormality on physical examination. The patient didn’t receive relevant past interventions. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed small nodules in the upper lobe of the right lung and local stenosis and occlusion of the anterior segmental bronchus. A miliary focus was present in the upper lobe of the left lung, and reexamination was recommended as multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the mediastinum and right hilum and tumor metastasis could not be excluded (Figure 1). Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT showed a nodule at the opening of the apical segmental bronchus of the upper lobe of the right lung indicating central lung cancer and enlarged lymph nodes were observed in the mediastinum indicating tumor metastasis (Figure 2). Fiberoptic bronchoscopy showed a neoplasm in a subsegment of the upper lobe of the right lung and biopsy confirmed squamous cell carcinoma of the upper lobe of the right lung (Figure 3). The patient was subsequently diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the right upper lung, with lymph node metastasis in the mediastinum (CT1N2M0, IIIA). Preoperative adjuvant treatment is routinely administered to patients in this stage and this patient chose preoperative neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy. Between late July and mid-August, he received TP combined immunotherapy 2 cycles of preoperative neoadjuvant therapy. The chemotherapy regimens were as follows: intravenous drip of 210 mg paclitaxel liposome on day 1,100 mg pembrolizumab on day 1, and 40 mg cisplatin on day 1–3. Three weeks later a chest CT reexamination showed small nodules in the upper lobe of the right lung and local stenosis and occlusion of the anterior segmental bronchus of its upper lobe. The focus was significantly shrunken in size compared with the initial findings and was not obvious during the examination. Multiple lymph nodes in the mediastinum and right hilum were smaller than previously seen (Figure 4). One month later, fiberoptic bronchoscopy reexamination showed no obvious lesions in the lumen of the upper lobe of the right lung. The patient then underwent thoracoscopic radical resection of right upper lung cancer under general anesthesia and intraoperative video-assisted thoracoscopy showed an adhered chest cavity without malignant pleural effusion. The tumor was no longer obvious and lymph nodes were observed in the upper mediastinum and lung hilum. Postoperative pathological examination indicated the following: right lung malignant tumor after chemotherapy. (I) (Upper right) Focal degeneration and necrosis of lung tissue. Alveolar epithelium hyperplasia. Hyperplasia, collagenization and inflammatory infiltration in interstitial fibrous tissue. (II) Lymph nodes of the bronchial root of the right upper lung [1], surrounding the bronchus of the right upper lung [1], station 2 [4], station 4 [6], station 7 [3] and station 10 [1], developed chronic inflammation, and some lymph nodes showed foam-like histiocytes and multinucleated giant cell reaction insides (considering the changes after chemotherapy) (Figure 5). After surgery, the patient recovered well without complications or sequelae and continued to receive monthly immunotherapy. Six months later, his chest CT and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed no tumor recurrence.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this study and any accompanying images. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013).

Discussion

Despite the successful development of systemic therapy, surgery remains the most effective treatment and the only possible radical cure for lung cancer. While neoadjuvant (preoperative) treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are also often used, until recently immune checkpoint blockade has had limited application. However, neoadjuvant immunotherapy may have prominent advantages as it enhances the effects of tumor immunity; that is, antigen exposure will greatly enhance the degree and duration of the tumor-specific T cell response while the primary tumor is still present (13). In contrast to surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, tumor immune checkpoint blockade activates the antitumor effect of tumor-specific T cells by blocking the inhibitory signaling pathway between T lymphocytes and antigen presenting cells. Its main targets include cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4), PD-1/PD-L1, B and T cell lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA), V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA), TIM-3, etc. (14). Resent research suggests that the preoperative tumor contains many cells that express immune checkpoint blockade targets, and a large number of tumor antigens facilitate the activation of enormous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes during immunotherapy, leading to a lasting antitumor effect. The systemic immune response induced before surgery can produce long-term immune memory and prevent tumor recurrence. But after surgery, patients fail to produce immune-mediated sustained antitumor effects owing to tumor resection (15).

Due to an aging population and advances in cancer treatment, the global population of patients with advanced lung cancer is increasing (16). Despite its high incidence in elderly individuals, clinical trials of lung cancer-related drugs have not yielded satisfactory results among these patients (17-19). Although age itself is not an exclusion criterion, elderly patients have certain limitations to enter clinical trials due to their decreased tolerance to treatment, poor organ reserve function, past complications, possible contraindications of continuous treatment, and potential differences in drug metabolism (20). While there are currently many clinical studies on neoadjuvant immunotherapy, few have indicated benefits for elderly patients. However, some evidence generated by subgroup analysis has been encouraging. A meta-analysis of immunotherapy alone among elderly patients (>75 years old) (21) included those with high PD-L1 expression and NSCLC who had not received treatment. This study revealed that pembrolizumab exhibited an improved OS compared with chemotherapy in the PD-L1 tissue polypeptide-specific antigen (TPS) >1% and >50% groups, which was consistent with the results from other populations including young patients. Pembrolizumab had comparable and better safety than chemotherapy in both elderly and young patients without increasing toxicity and showed no grade 5 immune-mediated adverse reactions among elderly patients, which supported the use of pembrolizumab monotherapy for advanced NSCLC patients (>75 years old) with PD-LI expression. Since single-drug immunotherapy is effective and safe for patients with advanced lung cancer, it could be reasonable that neoadjuvant therapy would result in identical therapeutic effects in patients with a better general condition. The NADIM study is a single-arm multicenter clinical study designed to explore the therapeutic effect of immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy in patients with stage IIIA NSCLC. Its latest results detail an experimental group which was administered nivolumab + paclitaxel + carboplatin (3 weeks) before operation. It is worth noting that the surgery was performed 3–4 weeks after neoadjuvant therapy, and nivolumab was continued for 1 year after surgery. Until May 2019, 46 patients were included in the study, and a total of 41 patients underwent surgery. The results showed that the MPR rate was 83%, the pCR rate was 71% and 38 cases (93%) exhibited downstaging after neoadjuvant therapy. The imaging evaluation according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines showed that the partial response (PR) rate was 71%, and the complete response (CR) rate was 7% (8). Intention to treatment (ITT) showed that 18 months after operation, the disease-free survival (DFS) rate of patients was 81% (95% CI: 61–91%), and the OS rate was 91% (95% CI: 73–97%). This potent therapeutic effect was combined with good safety. However, only a few middle-aged and elderly patients were included in that study resulting in limited date being made available on neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy in elderly patients.

The patient in the present study adopted neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy and obtained a good therapeutic effect. Studies have shown that chemotherapy can increase the immunogenicity of tumor cells, making tumor cells more likely to be attacked by immune cells, resulting in a synergistic anti-tumor effect (22). The patient’s focus and enlarged lymph nodes shrank significantly, and postoperative pathology showed CR. This patient had a smooth treatment process, and no immune-related adverse reactions were observed. Our case report indicates that for elderly patients with lung cancer, neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy can not only achieve an excellent therapeutic effect but can also be safe. We suggest this strategy is worthy of further clinical study with a larger sample size to obtain more rigorous results.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-7767

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-7767). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this study and any accompanying images. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zheng RS, Sun KX, Zhang SW, et al. Report of cancer epidemiology in China, 2015. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2019;41:19-28. [PubMed]

- Davidoff AJ, Tang M, Seal B, et al. Chemotherapy and survival benefit in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2191-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:39-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burdett S, Pignon JP, Tierney J, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for resected early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015.CD011430. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burdett S, Rydzewska LH, Tierney JF, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer--authors' reply. Lancet 2014;384:233. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. Five-year survival outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma treated with pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-001. Ann Oncol 2019;30:582-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forde PM, Smith KN, Chaft JE, et al. NSCLC, early stage Neoadjuvant anti-PD1, nivolumab, in early stage resectable non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2016;27:VI576. [Crossref]

- Provencio M, Nadal E, Insa A, et al. Neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy for the treatment of stage IIIA resectable non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A phase II multicenter exploratory study-Final data of patients who underwent surgical assessment. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 8509.

- Marosi C, Köller M. Challenge of cancer in the elderly. ESMO Open 2016;1:e000020. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quinten C, Coens C, Ghislain I, et al. The effects of age on health-related quality of life in cancer populations: A pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 involving 6024 cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:2808-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Li D, Yuan Y, et al. Functional versus chronological age: geriatric assessments to guide decision making in older patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:e305-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ventura MT, Casciaro M, Gangemi S, et al. Immunosenescence in aging: between immune cells depletion and cytokines up-regulation. Clin Mol Allergy 2017;15:21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Discov 2018;8:1069-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:252-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keung EZ, Ukponmwan EU, Cogdill AP, et al. The Rationale and Emerging Use of Neoadjuvant Immune Checkpoint Blockade for Solid Malignancies. Ann Surg Oncol 2018;25:1814-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:271-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Talarico L, Chen G, Pazdur R. Enrollment of elderly patients in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: a 7-year experience by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:4626-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh H, Kanapuru B, Smith C, et al. FDA analysis of enrollment of older adults in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: a 10-year experience by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, J Clin Oncol 2017;35:abstr 10009.

- Pang HH, Wang X, Stinchcombe TE, et al. Enrollment Trends and Disparity Among Patients With Lung Cancer in National Clinical Trials, 1990 to 2012. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3992-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Denson AC, Mahipal A. Participation of the elderly population in clinical trials: barriers and solutions. Cancer Control 2014;21:209-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nosaki K, Saka H, Hosomi Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in elderly patients with PD-L1-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Pooled analysis from the KEYNOTE-010, KEYNOTE-024, and KEYNOTE-042 studies. Lung Cancer 2019;135:188-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu J, Waxman DJ. Immunogenic chemotherapy: Dose and schedule dependence and combination with immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2018;419:210-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editor: B. Draper)