Primary small bowel melanomas: fact or myth?

Introduction

Primary small bowel malignant melanoma is rare, with a paucity of published reports. Whether these lesions arise as true small bowel primaries or represent metastases from unidentified cutaneous melanomas remains debatable. Similar to most small bowel tumors, small bowel melanoma (SBM) is typically difficult to diagnose, due to non-specific symptoms and difficult endoscopic access. The following report illustrates a case of SBM presenting with non-specific constitutional symptoms and upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old Caucasian man was referred by his General Practitioner to his local Gastroenterology service with fatigue and iron-deficiency microcytic anemia (Hb =8.5 g/dL; MCV =76 fL; Serum ferritin =6 ng/mL). Additionally, the patient reported an isolated episode of melena on a background of chronic diarrhea without unintentional weight loss or anorexia.

His past medical history was notable for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), first-degree hemorrhoids and a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), which was treated two years previously with coronary angioplasty and stenting of the right and left anterior descending coronary arteries. He received regular aspirin, clopidogrel, simvastatin, perindopril and bisoprolol. His family and social histories were unremarkable.

On hospital admission, general physical examination revealed pallor without jaundice or lymphadenopathy. Abdominal, rectal examination and proctoscopy were unremarkable.

Laboratory investigations yielded Hb levels of 7.0 g/dL, a MCV of 72 fL and serum ferritin levels of 6ng/ml, thus confirming iron-deficiency microcytic anemia. Tumor marker assays (CEA, CA19-9, and PSA) fell within normal limits, and celiac serology was negative.

Abdominal ultrasonography (US), esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy revealed no pathology. During his inpatient stay, the patient developed melena and sepsis with acute kidney injury (AKI). Additional investigations revealed serum urea and creatinine levels of 43 mmol/dL and 730 μmol/dL respectively, alongside Hb and white blood cell (WBC) levels of 6.5 g/dL and 23,000/mm3 respectively. Stool cultures isolated salmonella typhi. For this acute deterioration, the patient received cephalosporin treatment, intravenous fluids and two units of packed red cells, correcting the Hb to 10.9 g/dL. On stabilization and full recovery, he was discharged home for outpatient follow-up.

Within a few days however, he was readmitted with fever, melena, Hb levels of 8.3 g/dL and raised inflammatory markers (WBC =21,000/mm3; CRP =211 mg/L). A new murmur was detected, with negative transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms. Blood and stool cultures, as well as hemolysis, autoantibody (ANA & ANCA) and HIV screening was negative.

Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated several sub-centimeter mesenteric lymph nodes and thickening of the small intestine and descending colon, but did not reveal any specific pathology (Figure 1).

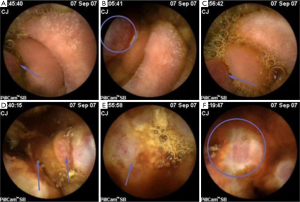

Consequently, video capsule endoscopy (VCE) was performed, which identified an unequivocal sessile jejunal tumor with contact bleeding (Figures 2,3).

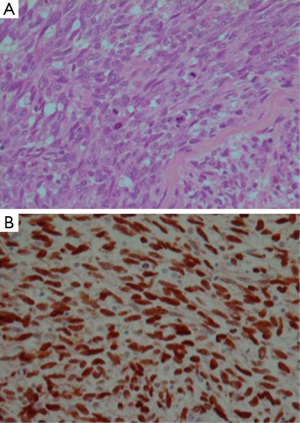

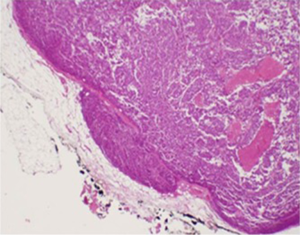

Exploratory laparotomy confirmed a mid-jejunal tumor without intra-abdominal metastases. Limited small bowel resection with end-to-end anastomosis and mesenteric lymph node sampling was performed. Postoperatively, a deep cervical lymph node was identified and excised. Immunohistochemistry of tissue biopsies revealed positive staining for melanoma markers S100, Melan-A, HMB45 and MIB1 (80% of cells) whereas chromogranin A, cytokeratin and CEA staining was negative (Figure 4). Further immunohistochemistry, with an identical staining pattern, identified infiltration by metastatic cancer cells within two out of seven mesenteric lymph nodes. Histology of both mesenteric and cervical lymph nodes confirmed the presence of invasive malignant melanoma (Figure 5).

Given the above findings, a thorough examination of skin, scalp, oral mucosa, eyes and genital areas was carried out but failed to identify any suspicious lesions or dysplastic nevi. Retrospective scrutiny of medical records revealed that 26 years earlier, the patient underwent excision of a benign mole from the left arm. At that time, histopathological analysis revealed a cellular non-dysplastic nevus with partial regression and potential tendency towards malignancy but during six years of regular follow-up, there were no recurrences and the patient was therefore discharged from the dermatology clinic.

From one month postoperatively onwards, the patient was readmitted on multiple occasions, initially with sepsis, and subsequently with ileus. At four months postoperatively he developed spastic paraparesis and severe pneumonia which prompted CT of the head, chest, abdomen and pelvis along with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. Imaging confirmed multiple brain, lung and bone metastases. Prior to any palliative treatment, the patient died of progressive disease and sepsis.

Discussion

Malignant melanomas are relatively common cancers making up around 2% of all tumors (2-4). The vast majority of melanomas are cutaneous but non-cutaneous tumors such as ocular, leptomeningeal, oral, nasopharyngeal, esophageal, bronchial, vaginal, anorectal and nail-bed melanomas (in descending order of frequency) occur, albeit very rarely (4,5). Only 3–4% of all melanomas originate in mucosal membranes as primaries (6).

GI tract malignant melanoma is rare and may either represent metastasis from a primary cutaneous site or a true primary tumor arising from the GI mucosa. Certain experts believe that primary intestinal melanomas derive from melanoblastic neural crest cells which migrate via the omphalomesenteric canal to the distal ileum whereas others postulate that these tumors originate from enteric neuroendocrine non-cutaneous tissue in the form of amine precursor uptake decarboxylase (APUD) cells that have undergone neoplastic transformation (7,8). The former hypothesis could certainly explain the presence of melanomas in the ileum whereas the latter would also account for the remaining non-ileal intestinal malignant melanomas (9). Other authors suggest that the cancer cells arise from neuroblastic Schwann cells of the intestinal autonomic nervous system (10). However, the most intriguing theory is that primary small intestinal melanomas do not exist as a distinct clinical entity but are instead secondary deposits from a primary cutaneous melanoma which has either regressed or remained indolent and undiagnosed (6,11,12).

Malignant melanoma is the commonest malignancy to metastasize to the GI tract (2,3). Although GI tract metastases are observed in up to 50–60% of malignant melanomas, clinical evidence of GI involvement with ante-mortem diagnosis comes to light in only 1–5% of cases (13-17). Interestingly, an estimated 10–26% of primary GI melanomas in fact represent metastases from occult cutaneous sites, and even in cases with a known primary site of malignant melanoma, GI metastases are discovered after an average of 54 months (and perhaps as long as 15 years later), if at all (16,18).

Malignant melanoma is also the commonest cancer to specifically metastasize to small bowel, comprising 50–70% of small bowel secondary cancers (19). Furthermore, although melanoma can metastasize to any GI tract site from mouth to anus, the jejunum and ileum, are most commonly involved (14). This might be partly attributed to the fact that melanoma cells show significant surface expression of the chemokine receptor CCR9, which might promote transmigration and homing of tumor cells to the small intestine, where the CCR9 ligand, CCL25, is strongly expressed (20).

In contrast to secondary metastases, primary SBM is exceptional. An extensive literature review identified only 26 reports describing potential cases of SBM based on the absence of a cutaneous or other primary site (Table 1). Biologically, the rarity of such tumors is not unexpected and can be explained by the lack of melanocytes in the small intestine; this is in contrast to the anorectum and even the esophagus where these cells are often naturally present (6,21,22).

Full table

It is currently challenging to differentiate between primary and secondary SBM (6,7). The clinical importance of this distinction lies within the differential in prognosis. Prognosis is worse for primary intestinal melanomas which tend to grow faster and more aggressively than metastatic tumors perhaps due to the rich lymphovascular supply available in the intestinal mucosa (46). In terms of prognosis, both primary and secondary GI malignant melanomas are worse than the conventional cutaneous equivalents, with a 5-year survival of only 10% and median survival of 4–6 months (4,12,23).

Criteria devised to support the diagnosis of true primary melanomas of the small intestine consist of:

- The existence of a single solitary tumor in the intestinal mucosa;

- The presence of other intramucosal melanocytic lesions in the surrounding intestinal epithelium;

- The absence of cutaneous or mucosal malignant melanoma or other atypical melanocytic skin lesions such as dysplastic nevi (14).

In contrast to primary GI melanoma, which is characteristically solitary, GI metastases from cutaneous melanoma are often multiple and co-existent with metastases to additional systems. The presence of melanophages and lymphocytic infiltration along with neovascularisation and healing fibrosis in the dermis provides additional histological evidence of a previous primary cutaneous malignant melanoma which metastasized to the small intestine before spontaneously regressing (6). Secondary small intestinal melanoma can be infiltrating, polypoid, cavitating or exoenteric and any type can be either pigmented or non-pigmented (47).

Clinical diagnosis of SBM is difficult, due to the non-specific nature of its symptoms and signs. Non-specific GI features include rectal bleeding (melena, hematochezia, and occult blood), which is the commonest symptom, along with chronic persistent abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss and asymptomatic anemia. Acute presentations with intussusception and perforation are rare; nevertheless, an awareness of these possibilities is important (20,48-53). Endoscopy and colonoscopy almost universally fail to identify small intestine pathology as reported in all the cases reviewed in the literature (Table 1). Alternative diagnostic modalities must be considered, such as US, CT, barium/technetium studies, positron emission tomography (PET) and capsule endoscopy, the latter of which permitted a diagnosis in this case.

VCE is a reliable, safe, minimally invasive diagnostic tool for small bowel disease with excellent diagnostic yield and is considered the gold-standard small intestine imaging modality (54,55). Our literature review suggests that men are more frequently affected than women, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.8 (20 vs. 11 cases), and that the ileum (n=20; 50%) and jejunum (n=10; 42%) are the most commonly involved GI sites (Table 1). There was only one case of solitary duodenal involvement, and one case that was considered as a primary SBM despite GI multifocality (Table 1). Although VCE can provide extremely useful information, in the absence of approachable extra-intestinal lesions, a tissue diagnosis of jejunal or ileal melanoma can only be achieved surgically.

Therapeutics in SBM are a field in need of development. Chemotherapy, immunotherapy and target therapy all have a role in medical treatment of SBM but they are almost invariably used palliatively. In cases of bowel obstruction, perforation or significant bleeding, emergency laparotomy for resection is mandatory. Nevertheless, the influence of surgery on morbidity and mortality is unclear. According to one study, neither elective nor emergency operations for secondary GI melanoma had any effect on postoperative morbidity or mortality (56). On the other hand, two separate studies reported that surgical intervention significantly reduced mortality and also suggested that complete resection (with histological evidence) was superior to incomplete removal in terms of mean survival (31.6–48.9 vs. 5.4–9.6 months) (57,58). In this context, clinical guidelines recommend that resection of the affected intestine should be wide with suitable margins of normal bowel proximal and distal to the lesion, and should include resection of the associated affected mesentery and lymph nodes (21). The relevant data from Table 1 in our study show that 1-year survival post resection was only 50% (8/16 cases), with half of the operated patients dying within a year postoperatively, as a result of tumor recurrence and/or progression.

In conclusion, primary SBM is a rare entity, which can exist asymptomatically for long periods of time and as such, is often diagnosed at an advanced stage, where treatment options are limited. The pathophysiology remains debatable. In our case, the possibility of a regressed or unidentified extra-intestinal site cannot be absolutely excluded. Whether or not primary SBM is a true entity remains to be clarified. Nevertheless, clinicians including Dermatologists, Gastroenterologists, General Practitioners, General Surgeons, Oncologists and Radiologists should maintain a degree of vigilance when encountering vague presentations suggestive of upper GI malignancy. As with any malignancy, a timely and accurate diagnosis affords patients with more therapeutic options.

Learning points

- Cutaneous melanoma can metastasize to any site in the GI tract, the commonest being the jejunum and ileum;

- GI melanomas are rare, and their true identity, whether primary or secondary, remains to be clarified;

- GI melanoma can present insidiously and non-specifically, evading common diagnostic modalities;

- A degree of suspicion in unexplained anemia and melena can expedite the diagnosis of GI melanoma;

- Capsule endoscopy is a safe, minimally invasive and high-yielding investigation for small bowel pathology.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

- Hadjinicolaou AV, Hadjittofi C, Athanasopoulos PG, et al. Capsule endoscopy video showing the sessile small bowel tumour. Asvide 2016;3:191. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/947

- Reintgen DS, Thompson W, Garbutt J, et al. Radiologic, endoscopic, and surgical considerations of melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. Surgery 1984;95:635-9. [PubMed]

- Reintgen DS, Thompson W, Garbutt J, et al. Radiologic, endoscopic and surgical considerations of malignant melanoma metastatic to the small intestine. Curr Surg 1984;41:87-9. [PubMed]

- Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: a summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer 1998;83:1664-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woollons A, Derrick EK, Price ML, et al. Gastrointestinal malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol 1997;36:129-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poggi SH, Madison JF, Hwu WJ, et al. Colonic melanoma, primary or regressed primary. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000;30:441-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amar A, Jougon J, Edouard A, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1992;16:365-7. [PubMed]

- Krausz MM, Ariel I, Behar AJ. Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine and the APUD cell concept. J Surg Oncol 1978;10:283-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manouras A, Genetzakis M, Lagoudianakis E, et al. Malignant gastrointestinal melanomas of unknown origin: should it be considered primary? World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:4027-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mishima Y. Melanocytic and nevocytic malignant melanomas. Cellular and subcellular differentiation. Cancer 1967;20:632-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elsayed AM, Albahra M, Nzeako UC, et al. Malignant melanomas in the small intestine: a study of 103 patients. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:1001-6. [PubMed]

- Schuchter LM, Green R, Fraker D. Primary and metastatic diseases in malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Oncol 2000;12:181-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Backman H. Metastases of malignant melanoma in the gastrointestinal tract. Geriatrics 1969;24:112-20. [PubMed]

- Blecker D, Abraham S, Furth EE, et al. Melanoma in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:3427-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ihde JK, Coit DG. Melanoma metastatic to stomach, small bowel, or colon. Am J Surg 1991;162:208-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDermott VG, Low VH, Keogan MT, et al. Malignant melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;166:809-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reintgen DS, Cox C, Slingluff CL Jr, et al. Recurrent malignant melanoma: the identification of prognostic factors to predict survival. Ann Plast Surg 1992;28:45-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wysocki WM, Komorowski AL, Darasz Z. Gastrointestinal metastases from malignant melanoma: report of a case. Surg Today 2004;34:542-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Macbeth WA, Gwynne JF, Jamieson MG. Metastatic melanoma in the small bowel. Aust N Z J Surg 1969;38:309-15. [PubMed]

- Tsilimparis N, Menenakos C, Rogalla P, et al. Malignant melanoma metastasis as a cause of small-bowel perforation. Onkologie 2009;32:356-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Atmatzidis KS, Pavlidis TE, Papaziogas BT, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine: report of a case. Surg Today 2002;32:831-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kadivar TF, Vanek VW, Krishnan EU. Primary malignant melanoma of the small bowel: a case study. Am Surg 1992;58:418-22. [PubMed]

- Timmers TK, Schadd EM, Monkelbaan JF, et al. Survival after resection of a primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine in a young patient: report of a case. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2013;7:251-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christova S, Meinhard K, Mihailov I, et al. Three cases of primary malignant melanoma of the alimentary tract. Gen Diagn Pathol 1996;142:63-7. [PubMed]

- Khosrowshahi E, Horvath W. Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine--a case report. Rontgenpraxis 2002;54:220-3. [PubMed]

- Kogire M, Yanagibashi K, Shimogou T, et al. Intussusception caused by primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine. Nihon Geka Hokan 1996;65:54-9. [PubMed]

- Krüger S, Noack F, Blöchle C, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the small bowel: a case report and review of the literature. Tumori 2005;91:73-6. [PubMed]

- Lizasoain Urcola J, González Sanz-Agero P, De Castro Carpeño J, et al. Melanoma of the small intestine and adenocarcinoma of the colon. Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995;18:323-5. [PubMed]

- Mittal VK, Bodzin JH. Primary malignant tumors of the small bowel. Am J Surg 1980;140:396-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramadan E, Mittelman M, Kyzer S, et al. Unusual presentation of malignant melanoma of the small intestine. Harefuah 1992;122:634-5, 687. [PubMed]

- Raymond AR, Rorat E, Goldstein D, et al. An unusual case of malignant melanoma of the small intestine. Am J Gastroenterol 1984;79:689-92. [PubMed]

- Sørensen YA, Larsen LB. Malignant melanoma in the small intestine. Ugeskr Laeger 1998;160:1480-1. [PubMed]

- Tabaie HA, Citta RJ, Gallo L, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine: report of a case and discussion of the APUD cell concept. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1984;83:374-7. [PubMed]

- Wade TP, Goodwin MN, Countryman DM, et al. Small bowel melanoma: extended survival with surgical management. Eur J Surg Oncol 1995;21:90-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yanar H, Coşkun H, Aksoy S, et al. Malign melanoma of the small bowel as a cause of occult intestinal bleeding: case report. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2003;9:82-4. [PubMed]

- Yashige H, Horishi M, Suyama Y, et al. A primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine. Gan No Rinsho 1990;36:955-8. [PubMed]

- Kim W, Baek JM, Suh YJ, et al. Ileal malignant melanoma presenting as a mass with aneurysmal dilatation: a case report. J Korean Med Sci 2004;19:297-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crippa S, Bovo G, Romano F, et al. Melanoma metastatic to the gallbladder and small bowel: report of a case and review of the literature. Melanoma Res 2004;14:427-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guraya SY, Al Naami M, Al Tuwaijri T, et al. Malignant melanoma of the small bowel with unknown primary: a case report. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2007;19:63-5. [PubMed]

- Iijima S, Oka K, Sasaki M, et al. Primary jejunal malignant melanoma first noticed because of the presence of parotid lymph node metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:319-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katsourakis A, Noussios G, Alatsakis M, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine: a case report. Acta Chir Belg 2009;109:405-7. [PubMed]

- Resta G, Anania G, Messina F, et al. Jejuno-jejunal invagination due to intestinal melanoma. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:310-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kumari NS, Nandyala VN, Devi KR, et al. Primary jejunal malignant melanoma presenting as intussusception: a rare case report. Int Surg J 2014;1:181-4. [Crossref]

- Sachs DL, Lowe L, Chang AE, et al. Do primary small intestinal melanomas exist? Report of a case. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;41:1042-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schoneveld M, De Vogelaere K, Van De Winkel N, et al. Intussusception of the small intestine caused by a primary melanoma? Case Rep Gastroenterol 2012;6:15-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liang KV, Sanderson SO, Nowakowski GS, et al. Metastatic malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Mayo Clin Proc 2006;81:511-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bender GN, Maglinte DD, McLarney JH, et al. Malignant melanoma: patterns of metastasis to the small bowel, reliability of imaging studies, and clinical relevance. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:2392-400. [PubMed]

- Mucci T, Long W, Witkiewicz A, et al. Metastatic melanoma causing jejunal intussusception. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:1755-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alwhouhayb M, Mathur P, Al Bayaty M. Metastatic melanoma presenting as a perforated small bowel. Turk J Gastroenterol 2006;17:223-5. [PubMed]

- Brummel N, Awad Z, Frazier S, et al. Perforation of metastatic melanoma to the small bowel with simultaneous gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:2687-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cholakov O, Stefanov P, Beliaev O, et al. Disseminated malignant melanoma, complicated with perforation of the small intestine and peritonitis. Khirurgiia (Sofiia) 2003;59:44-5. [PubMed]

- Cholakov O, Tsekov Kh, Beliaev O, et al. Disseminated malignant melanoma, complicated with upper-digestive hemorrhage. Khirurgiia (Sofiia) 2003;59:52-3. [PubMed]

- Klausner JM, Skornick Y, Lelcuk S, et al. Acute complications of metastatic melanoma to the gastrointestinal tract. Br J Surg 1982;69:195-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prakoso E, Selby WS. Polypoid and non-pigmented small-bowel melanoma in capsule endoscopy is common. Endoscopy 2010;42:979; author reply 980. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan MI, Johnston M, Cunliffe R, et al. The role of capsule endoscopy in small bowel pathology: a review of 122 cases. N Z Med J 2013;126:16-26. [PubMed]

- Gutman H, Hess KR, Kokotsakis JA, et al. Surgery for abdominal metastases of cutaneous melanoma. World J Surg 2001;25:750-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Branum GD, Seigler HF. Role of surgical intervention in the management of intestinal metastases from malignant melanoma. Am J Surg 1991;162:428-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ollila DW, Essner R, Wanek LA, et al. Surgical resection for melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. Arch Surg 1996;131:975-9; 979-80.