Robotic-assisted left upper lingual segmentectomy

Clinical data

Medical history

The patient, a 50-year-old woman, was admitted due to “repeated hemoptysis for more than half a year” and “bronchiectasis”. The patient began to cough up blood without obvious causes about 6 months ago. The blood was bright red in color, and the patient spitted about 6 times during each attack. No special treatment was given. She spitted up 9 times of fresh blood again 1 month ago and then visited a local hospital. Chest CT showed that the lingular bronchus of left upper lobe showed cystic and cylindrical dilatation, along with thickened walls. Small dotted and patchy intensities were visible around it. Left bronchial dilation accompanied with peribronchitis was considered. The condition was not remarkably improved after anti-inflammatory and hemostatic treatment. She then visited our hospital for further management. After outpatient consultation, she was admitted due to “bronchiectasis”. The patient’s complaints did not include cough, chest tightness, shortness of breath, low fever, night sweats, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, diarrhea, heart palpitations, or discomfort of precordial area. His mental status, physical performance, appetite, and sleep were normal, and the body weight did not obviously change. Urination and defecation were normal.

Initial physical examination findings included HR of 75 bpm, breath rate of 20 times per minute, and BP of 125/79 mmHg. The thoracic cage was symmetric and showed no deformity. The respiratory movement in both lungs was symmetric. The respiratory movement and respiratory frequency was normal. The vocal fremitus and voice transmission were normal in both lungs. Pleural friction fremitus was not palpable. There was no chest wall and rib tenderness. The sternum was not sensitive to percussion. Resonance was heard during percussion in both lungs. Cardiopulmonary examination showed no abnormal results.

The preliminary diagnosis was bronchiectasis.

Physical examination

The body temperature was 36.3 °C. Auscultation revealed harsh breath sounds in the left upper lung field; however, no dry or wet rales or pleural friction rubs were heard. No such abnormality was heard in other lobes. No other positive sign was detected.

Auxiliary examination

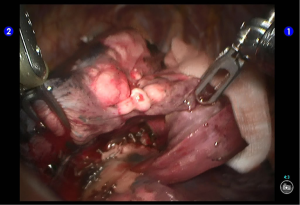

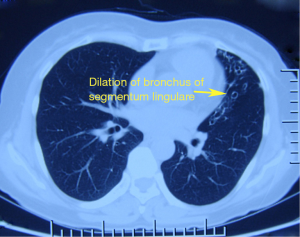

Chest CT: The lingular bronchus of left upper lobe showed cystic and cylindrical dilatation, along with thickened walls. Small dotted and patchy intensities were visible around it. Left bronchial dilation accompanied with peribronchitis was considered (Figure 1).

No obvious abnormality was found in ECG, echocardiography, pulmonary function test, blood gas analysis, and other biochemical tests.

Pre-operative preparation

Bronchiectasis was considered based on the symptoms, signs, and imaging findings.

The symptoms were remarkably alleviated after medical treatment; however, a clear lesion persisted and was confined to the lingular bronchus. Resection of lingual segment of the left upper pulmonary lobe or wedge resection of the upper lobe was then decided. Tests including sputum culture were performed before the surgery. Also, oral administration of anti-inflammatory and phlegm-eliminating drugs as well as atomization for sputum discharge was applied to control the amount of phlegm.

Surgical procedures

Anesthesia and body position

After the induction of general anesthesia, the patient was placed in a right lateral decubitus position under double-lumen endotracheal intubation. With her hands put in front of head, he was fixed in a Jackknife position with single-lung (right) ventilation (Figure 2).

Surgical procedures

Incisions. A 1.5-cm camera port was created in the 8th intercostal space (ICS) at left posterior axillary line, and two 1.0-cm working ports were separately made in the 5th ICS at left anterior axillary line and the 8th ICS at scapular line. A 4-cm auxiliary port was made in the 7th ICS at midaxillary line (Figure 3).

The robot Patient Cart were connected over the patient’s head. A 12-mm trocar was placed at the camera port in the 8th ICS at posterior axillary line to be attached with the camera arm. The robot metal trocars were respectively attached to the 2# arm (left hand) and 1# arm (right hand) at the incisions in the 5th ICS anterior axillary line and the 8th ICS scapular line. Incision protector was applied in the auxiliary port.

Inspection of the thoracic cavity showed that there were many cord-like structures adhered in the upper lobe. Under the endoscopic monitoring, the robot trocars were separately inserted via the two working ports. Incision protector was applied in the auxiliary port. The robot Patient Cart is positioned directly above the operating table and then connected. Its left hand was attached to bipolar cautery forceps, and its right hand was attached to a unipolar cautery hook. The cord-like structures were then dissected. Inspection also showed that the lesion was localized inside the lingual segment of the upper lobe.

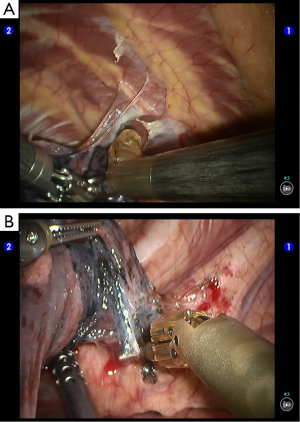

Segmentectomy. Divide the pleural adhesions (Figure 4).

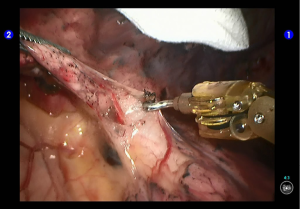

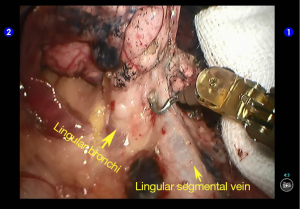

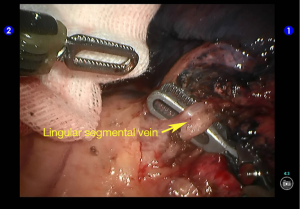

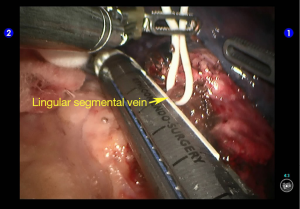

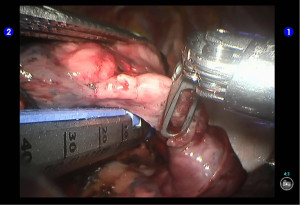

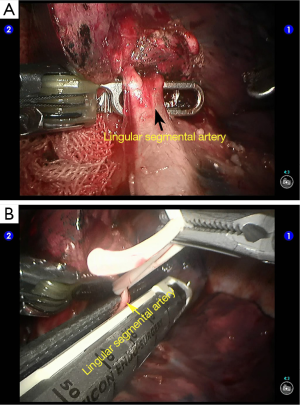

Cut open the oblique fissure to dissociate the lingular branch of the upper lobe pulmonary artery (Figures 5,6). The anterior mediastinal pleura were cut open to dissociate the lingular branch of the upper lobe pulmonary vein. The vein was handled firstly. Endoscopic cutter/stapler was inserted through the auxiliary port, and the vein was transected using a white reload (Figures 7,8), and then transect the lingular segmental artery using a white reload (Figure 9A,B).

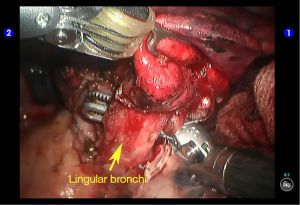

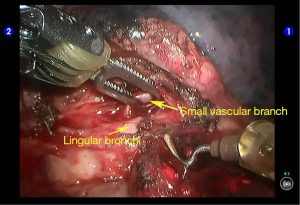

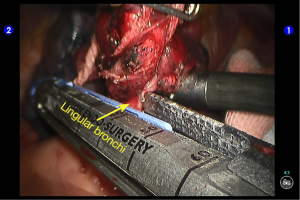

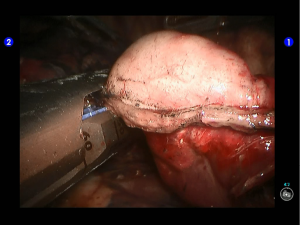

Dissociate the lingular segmental bronchus (Figure 10). Behind it there were small vascular branches, which were handled using cautery devices (Figure 11). Clamp the lingular segmental bronchus with a blue reload. An anesthesiologist was asked to suction sputum and ventilate the operated lung, so as to identify the borders of the lingular segment and ensure the proper segments of the upper lobe were well ventilated (Figures 12,13). Divide the bronchus. The inter-segmental gap was separated using two golden reloads and one blue reload, and thus the lingual segment was removed (Figures 14,15). A specimen bag was inserted via the auxiliary port to harvest the specimen. Wash the thoracic cavity. The residual lungs were well dilated, without air leakage. The trauma surfaces and the post-operative lung surfaces were sprayed and covered with the sol of Tistat absorbable hemostatic gauze. After the robot system was withdrawn, the thoracic drainage tube was indwelled at the camera port before closing the chest. Close the chest after lung recruitment.

Postoperative treatment

Postoperative treatment is similar to that after the conventional open lobectomy. The thoracic drainage tube was withdrawn 7 days after the surgery.

Pathological diagnosis

Bronchiectasis.

Comment

Anatomic segmentectomy is quite difficult. It may be considered in patients with begin tumors and with well-developed lung fissures. The key to a successful surgery includes: the operator is familiar with the anatomy of the segmental vessels and bronchus and can appropriately handle these structures after adequate dissociation; ventilating the lung after clamping the bronchus will not hurt the nearby bronchus; the borders among segments can be clearly identified. Some authors prefer to clamp the bronchus while the lung is half ventilated, so as to keep the inflation of the resected lung tissues, which is helpful to identify the segmental borders and thus make the transection using stapler easier. Their practices warrant further investigation in clinical settings.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.