Nipple-areola complex reconstruction in transgender patients undergoing mastectomy with free nipple grafts: a systematic review of techniques and outcomes

Introduction

In female-to-male transgender individuals pursuing gender affirming surgeries (GAS), the first surgical procedure is usually chest wall masculinization, also known as transmale top surgery (1,2). It is sometimes the only surgical step undertaken during transition and has been associated with improved self-esteem, body image and quality of life, having a positive impact on self-confidence, personal relationships and social interactions (1,3-5).

Several techniques have been described for chest wall masculinization surgeries. In general, the goal of transmale top surgery includes the complete or partial removal of breast tissue and skin excess, minimization of chest-wall scars, and appropriate reshaping and positioning of the nipple-areola complex (NAC) (6). The two most common surgical approaches are the inframammary fold and the periareolar techniques. Although these techniques have their own particular indications depending on breast size, skin elasticity and patient-surgeon discussion, recent data suggest that the transverse inframammary fold incision may have decreased rates of revision surgery and lower complication rates compared with the periareolar and other limited scar techniques (7).

Among the various techniques described in the literature, double-incision mastectomy (DIM) is the most common procedure for chest wall masculinization surgery in transgender and gender non-binary (TGNB) individuals (3). It consists of a total mastectomy through horizontal elliptical incisions. Usually, the NACs are harvested as full-thickness skin grafts and transferred onto its new, final location. Free nipple grafts (FNG) are a key component of the overall satisfaction and aesthetics of the procedure. Understanding the appropriate NAC characteristics, position, shape, and configuration could help enhance surgical techniques, and thus, positively impact patient satisfaction and aesthetic success of this procedure (8). In this study, we conducted a thorough systematic review of the literature to assess the different techniques and outcomes for FNG in TGNB patients undergoing DIM for chest wall masculinization.

We present the following article in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting checklist (9) (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-4522).

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they (I) were original clinical studies that had been published in English, Spanish, Chinese, French, Turkish, Portuguese, Arabic, and German languages since January 2000 to December 2019; (II) described the NAC reconstruction technique after double incision-mastectomy and FNG; (III) evaluated the surgical outcomes, or satisfaction, or aesthetic results after a minimum duration of follow-up of 6 months, and (IV) included at least 10 patients. Articles that included patients that underwent other mastectomy techniques, such as circumareolar approach, were also included only if they included 10 patients or more that underwent DIM-FNG. Studies including <10 patients were excluded, because we considered their sample sizes to be inadequate for assessing outcomes of interest. Studies with combined surgeries were also excluded, because we considered it can alter the overall outcomes.

Data sources and search strategies

A comprehensive search of several databases from 2000 to December 23rd, 2019 was conducted. The databases included Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, and Daily, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Ovid Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus.

The search strategy was designed and conducted by an experienced librarian with input from the study’s principle investigator. Controlled vocabulary supplemented with keywords was used to search for studies describing nipple grafting techniques in double incision mastectomy and was limited to English, Spanish, Chinese, French, Turkish, Portuguese, Arabic, and German languages. The actual strategy listing all search terms used and how they are combined is available in Appendix 1.

Assessment of study quality and risk of bias

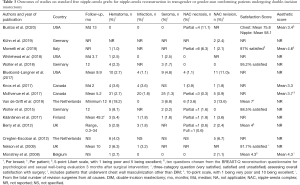

All articles included in the qualitative analysis were assessed for risk of bias with the use of the Quality Assessment Tools from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (10). Appraisal of each question in each tool provides a subjective assessment of the risk of bias, which we ranked as poor, fair or good, corresponding to high, moderate, and low risk of bias, respectively. A table summarizing the assessment of each included study can be found in Tables 1,2.

Full table

Full table

Data extraction

After obtaining the list of potential articles, duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers (S.S.B. and D.K.) screened titles and abstracts, full-texts, assessed quality, and extracted data. Any disagreements were discussed, and a third reviewer (O.J.M.) was available to arbitrate any issues that remained unresolved. A joint decision was made to determine the inclusion or exclusion. Data were extracted on the number of patients undergoing DIM-FNG, age, and body mass index (BMI), surgical technique for NAC reconstruction, surgical outcomes, patient satisfaction and aesthetic results. Additionally, the follow-up time was recorded.

Data analysis

Data were tabulated and presented in tables. The pooled number of patients that underwent DIM-FNG was obtained. The studies were divided in two groups depending on the NAC reconstruction technique: conventional FNG and alternative techniques for NAC reconstruction in FNG. A qualitative synthesis was performed. Due to the diversity of study designs and methods of each study, meta-analysis was not conducted.

Results

Search Results

The search yielded a total of 224 publications. We screened 219 unique titles and abstracts and selected 46 for full-text review (Figure 1). No additional study was identified from cross-referencing and hand-searching. Our cohort was added to the qualitative synthesis and tables. A total of 19 articles were included (Tables 1,2) (7,11-19,20-27).

Included studies

The included studies comprised a total of 1,587 patients (3,174 breasts). There were a total of 14 studies using the conventional FNG technique, 4 describing new approaches for NAC reconstruction in FNG and 1 study comparing the conventional FNG technique to another alternative technique. A total of 1,347 patients underwent DIM-FNG with conventional FNG and 240 underwent alternative techniques for NAC reconstruction after DIM-FNG. Tables 1,2 show the study characteristics of the included studies. Tables 3,4 show outcomes of interest of each study.

Full table

Full table

Standard free nipple-areola grafts for nipple-areola reconstruction

DIM is commonly indicated for medium-to-large size breasts with wide or large NAC, ptotic breasts or breasts with skin with poor elasticity. Conventional or standard FNG consist of en bloc removal of both NAC, resizing the areola and grafting them on the chest. In most studies using this technique, the NAC was configured in a circular shape and sized between 2 to 3 cm in diameter. The new position of the grafts varied between studies, but it was generally positioned as follows: the vertical axis was either along the lateral border of the pectoralis major border or along the original nipple line, and the horizontal axis at the level of 4th to 5th rib or 2 to 3 cm above the mastectomy scar/inferior border of the pectoralis major.

Postoperative complications were low. The rate of breasts that presented hematoma varied between 0% to 18.2%, the rate of seroma from 0 to 6.8%, and infection rate from 0% to 3.2%. Development of nipple necrosis (partial or full-thickness) varied from 0% to 11.1%. Up to 13.6% of patients required NAC revision surgeries. Patients had high satisfaction overall with good aesthetic outcomes.

Alternative techniques of free nipple-areola grafts for nipple-areola reconstruction

Alternative techniques for FNG have been proposed in an attempt to improve aesthetic results and patient satisfaction while maintaining safety. Three of the five studies describing novel techniques are composite NAC grafts, where the areola and the nipple are disassembled and resized separately, and then grafted. Another technique describes the use of a modified skate local flap used to create the neo-nipple. This technique uses free areolar graft from the native NACs to enclose the skate flap. One other technique describes the splitting of one of the native NACs into two halves. Each half is then converted into an oval shape and grafted to the chest. The de-epithelized recipient site is shaped as an oval in most of these studies.

Postoperative complications were also low in this cohort. The rate of breasts that presented hematoma varied between 0% to 5%, the rate of seroma from 0% to 2%, and infection rate from 0 to 1%. Development of nipple necrosis (partial or full-thickness) varied from 0% to 9.4%. Up to 10% of patients required NAC revision surgeries. Only two studies assessed satisfaction, which was reported as high, and only one (half split nipple sharing technique) evaluated aesthetic outcomes, which was reported with a median of 3.9 over a 5.0 scale.

Discussion

Chest wall masculinization has shown to have positive effects on quality of life and mental health, as it allows the individual to present more easily in congruence with their identity (7,28). It is critical to understand the different surgical techniques in order to provide the patient with superior aesthetic outcomes and higher satisfaction while maintaining the safety profile. DIM-FNG is the preferred method among plastic surgeons for various reasons of which include wide surgical exposure, its application to wide range of patient profile with breast variations, and flexibility in reshaping and repositioning the NACs despite the stigmatic scar (25).

The position and configuration of the NAC play a major role in patient satisfaction and aesthetics success. However, there is no consensus on the NAC size, shape and location in patients undergoing DIM-FNG, and techniques are highly heterogenous. In this study, we systematically reviewed the literature to find the various options for NAC reconstruction when performing DIM-FNG.

The location of the NAC in cis-male tends to be more lateral than cis-female individuals (29-31). Agarwal et al. (32) conducted an anatomic study analyzing 64 NACs in 32 volunteers with body mass index (BMI) of 25 or less; they found that the cis-male nipple was positioned on average 2.5 cm medial to the lateral border of the pectoralis muscle and 2.4 cm above the inferior pectoralis insertion (15,24,33,34). In our review, however, we found that, although most studies consider the pectoralis major lateral border and inferior insertion as the major landmarks, there is still no consensus as to how far from the lateral border or how much superior to the inferior insertion of the pectoralis major muscle the NACs should be placed. Moreover, a significant number of studies still use other less reliable reference points such as clavicle, ribs or existing nipple line. One study reported final NAC location by eye (26). Some authors find it is simpler and effective to utilize multiple superficial anatomic landmarks to reposition the NAC (24,32,33).

NAC shape and size are also major considerations. The cis-male NAC is usually oval with a horizontal/vertical diameter of 2.7:2.0 cm (31). Average normal nipple-to-areola ratio has been described to be 0.28 (29). Based on our review, NAC dimensions were constructed according to surgeon’s aesthetic judgement prior to the final NAC placement, and usually only the areola is resized and mamilla is not often mentioned. An adequate reconfiguration from the circular, larger cis-female NAC to more ovoid, smaller NAC with less mamilla projection should be accomplished.

During de-epithelization of the FNG, thinning and narrowing of the mammilla adequately reduces the size and projection of the mamilla. However, several authors have introduced new nipple reconstruction techniques in an attempt to obtain a more masculine NAC and to address large mamilla projection (14,16,23,32,35). These new techniques consist of two parts: (I) NAC harvest and reshaping and (II) de-epithelized recipient site configuration. For the former, the most common modification was to perform a composite FNG, where an areolar and a nipple graft are harvested separately, reshaped, and then transferred. Another option is to perform a component NAC reconstruction using a modified skate flap for nipple reconstruction and a surrounding free areolar graft from the excised native NAC (23,36). The advantage with the use of a local skate flap is the better nipple projection due to a thicker base, and a natural appearing areola due to the free areolar graft. Another option is the half split sharing technique, which consists on splitting one of the harvested native NAC into two halves and reconfiguring each into an oval shaped new NAC. This creates a natural nipple projection, smaller, oval NACs and preserves the nipple-to-areola ratio (27). Regarding the de-epithelized recipient site, most studies describe a circular incision. However, to avoid the natural tendency for the grafted NACs to elongate vertically after scarring, some authors use a horizontal oval incision in the recipient site (32). Other techniques that are out of the scope of this review, because they are not technically FNG, preserve the NAC attached to a dermal stalk or pedicle (15,35,37). These techniques include the buttonhole top surgery or the inverted-T top surgery, which preserve the NAC within a pedicle and avoids nipple grafts. However, the use of these options is usually associated with the development of a fuller chest and an increased thickness immediately below the nipple.

Conclusions

This review compiles the different techniques used for NAC reconstruction in TGNB patients who undergo DIM-FNG. Newer techniques aim to reshape the new NACs in an oval shape, reduce nipple size and localize the NACs using the pectoralis major lateral and inferior border as reference. In addition, a horizontal oval incision at the recipient site may avoid an undesired vertical NAC.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Dr. Oscar J. Manrique, Dr. John A Persing, and Dr. Xiaona Lu) for the series “Transgender Surgery” published in Annals of Translational Medicine. The article was sent for external peer review organized by the Guest Editors and the editorial office.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-4522

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-4522). The series “Transgender Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. OJM served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Claes KEY, D’Arpa S, Monstrey SJ. Chest Surgery for Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Individuals. Clin Plast Surg 2018;45:369-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lane M, Ives GC, Sluiter EC, et al. Trends in Gender-affirming Surgery in Insured Patients in the USA. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2018;6:e1738 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilson SC, Morrison SD, Anzai L, et al. Masculinizing Top Surgery: A Systematic Review of Techniques and Outcomes. Ann Plast Surg 2018;80:679-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nelson L, Whallett EJ, McGregor JC. Transgender patient satisfaction following reduction mammaplasty. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2009;62:331-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Black CK, Fan KL, Economides JM, et al. Analysis of Chest Masculinization Surgery Results in Female-to-Male Transgender Patients: Demonstrating High Satisfaction beyond Aesthetic Outcomes Using Advanced Linguistic Analyzer Technology and Social Media. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2020;8:e2356 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hage JJ, van Kesteren PJM. Chest-Wall Contouring in Female-to-Male Transsexuals. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;96:386-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Donato DP, Walzer NK, Rivera A, et al. Female-to-Male Chest Reconstruction: A Review of Technique and Outcomes. Ann Plast Surg 2017;79:259-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shulman O, Badani E, Wolf Y, et al. Appropriate location of the nipple-areola complex in males. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;108:348-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). Study Quality Assessment Tools. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. [cited 2020 May 1]. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- Wolter A, Scholz T, Pluto N, et al. Subcutaneous mastectomy in female-to-male transsexuals: Optimizing perioperative and operative management in 8 years clinical experience. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2018;71:344-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bluebond-Langner R, Berli JU, Sabino J, et al. Top Surgery in Transgender Men: How Far Can You Push the Envelope? Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;139:873e-82e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whitehead DM, Weiss PR, Podolsky D. A Single Surgeon’s Experience with Transgender Female-to-Male Chest Surgery. Ann Plast Surg 2018;81:353-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knox ADC, Ho AL, Leung L, et al. A Review of 101 Consecutive Subcutaneous Mastectomies and Male Chest Contouring Using the Concentric Circular and Free Nipple Graft Techniques in Female-to-Male Transgender Patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;139:1260e-72e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolter A, Diedrichson J, Scholz T, et al. Sexual reassignment surgery in female-to-male transsexuals: An algorithm for subcutaneous mastectomy. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2015;68:184-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lo Russo G, Tanini S, Innocenti M. Masculine Chest-Wall Contouring in FtM Transgender: a Personal Approach. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2017;41:369-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kühn S, Keval S, Sader R, et al. Mastectomy in female-to-male transgender patients: A single-center 24-year retrospective analysis. Arch Plast Surg 2019;46:433-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van de Grift TC, Pigot GLS, Kreukels BPC, et al. Transmen’s Experienced Sexuality and Genital Gender-Affirming Surgery: Findings From a Clinical Follow-Up Study. J Sex Marital Ther 2019;45:201-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frederick MJ, Berhanu AE, Bartlett R. Chest Surgery in Female to Male Transgender Individuals. Ann Plast Surg 2017;78:249-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morselli PG, Summo V, Pinto V, et al. Chest Wall Masculinization in Female-to-Male Transsexuals: Our Treatment Algorithm and Life Satisfaction Questionnaire. Ann Plast Surg 2019;83:629-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cregten-Escobar P, Bouman MB, Buncamper ME, et al. Subcutaneous mastectomy in female-to-male transsexuals: a retrospective cohort-analysis of 202 patients. J Sex Med 2012;9:3148-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kääriäinen M, Salonen K, Helminen M, et al. Chest-wall contouring surgery in female-to-male transgender patients: A one-center retrospective analysis of applied surgical techniques and results. Scand J Surg 2017;106:74-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frey JD, Yu JZ, Poudrier G, et al. Modified Nipple Flap with Free Areolar Graft for Component Nipple-Areola Complex Construction: Outcomes with a Novel Technique for Chest Wall Reconstruction in Transgender Men. Plast Reconstr Surg 2018;142:331-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monstrey S, Selvaggi G, Ceulemans P, et al. Chest-wall contouring surgery in female-to-male transsexuals: A new algorithm. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;121:849-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McEvenue G, Xu FZ, Cai R, et al. Female-to-Male Gender Affirming Top Surgery: A Single Surgeon’s 15-Year Retrospective Review and Treatment Algorithm. Aesthet Surg J 2017;38:49-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berry MG, Curtis R, Davies D. Female-to-male transgender chest reconstruction: a large consecutive, single-surgeon experience. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2012;65:711-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bustos SS, Forte AJ, Ciudad P, et al. The Nipple Split Sharing vs. Conventional Nipple Graft Technique in Chest Wall Masculinization Surgery: Can We Improve Patient Satisfaction and Aesthetic Outcomes? Aesthetic Plast Surg 2020;44:1478-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Newfield E, Hart S, Dibble S, et al. Female-to-male transgender quality of life. Qual Life Res 2006;15:1447-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yue D, Cooper LRL, Kerstein R, et al. Defining Normal Parameters for the Male Nipple-Areola Complex: A Prospective Observational Study and Recommendations for Placement on the Chest Wall. Aesthet Surg J 2018;38:742-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lewin R, Amoroso M, Plate N, et al. The Aesthetically Ideal Position of the Nipple-Areola Complex on the Breast. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2016;40:724-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beer GM, Budi S, Seifert B, et al. Configuration and Localization of the NAC in Men. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;108:1947-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agarwal CA, Wall VT, Mehta ST, et al. Creation of an Aesthetic Male Nipple Areolar Complex in Female-to-Male Transgender Chest Reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2017;41:1305-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindsay WR. Creation of a male chest in female transsexuals. Ann Plast Surg 1979;3:39-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hage JJ, Bloem JJAM. Chest Wall Contouring for Female-to-Male Transsexuals: Amsterdam Experience. Ann Plast Surg 1995;34:59-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rothenberg KA, Tong WMY, Yokoo KM. Early Experiences with the Buttonhole Modification of the Double-Incision Technique for Gender-Affirming Mastectomies. Ann Plast Surg 2018;81:642-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vigneswaran N, Lim J, Lee HJ, et al. A novel technique with aesthetic considerations in female-to-male transsexuals nipple areola complex reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2013;66:1805-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kornstein AN, Cinelli PB. Inferior pedicle reduction technique for larger forms of gynecomastia. Aesthetic Plast Surg 1992;16:331-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]