Loose combined cutting seton for patients with high intersphincteric fistula: a retrospective study

Introduction

Fistula-in-ano, or anal fistula, is a common anorectal disease that causes considerable morbidity, which negatively impacts the quality of life of sufferers. The incidence of anal fistula is approximately 8% in Western countries and 3.6% in China (1-3). High anal fistula, which affects the upper two-thirds of the external sphincter, poses a significant challenge for surgeons (4). The core principal underlying the treatment of this difficult condition is to cure the fistula and prevent recurrence while maintaining the patient’s continence (1,5-7). Despite several alternative methods having been proposed for the treatment of high anal fistula, including advancement flap procedure, fistula plug, the use of fibrin glue sealants, and ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT), the rates of healing after surgery remain extremely low (5,7-9).

Seton techniques are often used in surgical procedures for high anal fistula due to their association with a higher cure rate and a lower rate of incontinence. Many different seton-based techniques currently exist, employing a wide variety of seton materials, insertion techniques, and mechanisms of action (5,9). Previous studies have reported recurrence rates ranging from 8–22% depending on the type of seton used; however, the choice of type of seton is always based on the surgeon’s personal preference (10-17). The loose seton technique facilitates drainage and promotes the development of a mature fistula track, without placing the sphincter at risk (5). However, this technique may result in persistence of the fistula through continuously stimulating fibrosis, leading to low rates of complete healing. Although the cutting (tight) seton, which gradually transects the external sphincter muscle, can completely cure fistula, it has consistently produced unacceptable rates of incontinence and severe pain (18-20).

Therefore, it is critical that the limitations of this common seton technique (loose seton technique) are urgently overcome to ensure that the function of anal sphincter muscles is protected in order to avoid incontinence while eliminating fistula, thus improving the quality of life for those patients. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a simple modification of the loose combined cutting seton (LCCS) technique in the treatment of high anal fistula. With the modification, we wish to achieve a high healing rate with an increased level of continence, as well as a low level of postoperative pain, in most patients with high anal fistula. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-6123).

Methods

Study design and patients

The medical records of consecutive patients with high anal fistula who underwent LCCS in our hospital between Mar 2014 and Jul 2017 were retrospectively reviewed. High anal fistula was diagnosed when a limb or track of the fistula passed above the highest muscle of continence (the anorectal ring or puborectalis muscle), regardless of whether the high track entered or ended outside the rectum, or reached high in the ischiorectal fossa or penetrated into the true pelvic cavity. Patients with fistula caused by inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or trauma were excluded. Patients suffering from severe diseases, such as malignant tumors, malnutrition, severe heart or lung diseases, cirrhosis, or renal failure were also excluded, as were pregnant or lactating women. Over the last two decades, many sphincter-preserving procedures for the treatment of anal fistula have been introduced with the goal of reducing the injury to the anal sphincters and preserving optimal function.

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient who agreed to participate in this study. The study was approved by ethics committee of China-Japan Hospital (No.: 2019-SFZX-7).

Treatment procedures

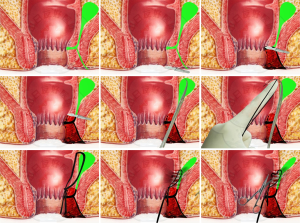

All procedures were carried out by the same surgeon (LHZ). The procedure for LCCS was performed as follows (Figure 1): under general or epidural anesthesia, patients were placed in the lateral position to allow access to the fistula. After routine disinfection with iodophor (0.5%), the operation towel was laid down, and the anal canal was sterilized after its relaxation. Digital rectal examination (with reference to the anorectal results on B ultrasound) was performed to determine the internal opening of the fistula, the scope of the fistula, the presence of branched tubes and dead canal tissue, and hard lumps spreading over the anorectal ring. Then, the probe was inserted from the external opening of the fistula; if the fistula had no external opening, the distal end of the fistula was cut based on its extension. The probe was passed through the internal opening, following the extension of the fistula wall, and cut the fistula wall layer by layer to open the fistula. The tissue surrounding the internal opening was cut until 0.5–1.0 cm away. The probe from the internal opening was passed upward through the fistula using curved hemostatic forceps guided by fingers stretching into the enteric cavity, and, finally, to the top of the fistula. The tip of the forceps was used to penetrate the stoma of the intestinal wall, which was the central point of the lumps in crisscross. After that, the fingers were removed, and four silk threads in No. 10 were tied to the fingertips at one end and inserted into the enteric cavity. Then, the threads were clamped by hemostatic forceps, pulled out of the stoma of the intestinal cavity along the fistula, tightened at both ends, and knotted for fixation.

Postoperatively, dressing was changed once a day after routine disinfection. Oil gauze and common gauze were used for drainage and fixation of the external application, respectively. All patients were prescribed intravenous analgesics (flurbiprofen axetil injection, 100 mg, QD) and intravenous antibiotics (etimicin sulfate and sodium chloride injection, 300 mL, QD) for 2 days. The ligature was loose on postoperative day 7; however, the loose seton was still continued for drainage. The silk thread was removed on postoperative day 20 depending on the conditions of granulation tissue growing in the fistula tract. After the thread was removed, the dressing was changed continuously until the incision was healed.

Data collection and outcome measures

Data collected included demographics, medical history, co-morbidities, details of the fistula, operative procedure, and prognosis. Before the surgical procedure, all patients were assessed by routine blood test, liver and renal function tests, and blood glucose and lipid profiles. Additionally, some patients also underwent endoanal ultrasonography and anorectal pressure (AP) manometry to identify the location of the internal opening and the shape of the fistula. During follow-up, all patients visited the outpatient clinic to undergo physical examination (including anal inspection and digital anal examination), endoanal ultrasonography, and anorectal manometry and at 2 months after surgery, anorectal manometry. However, if a patient developed unbearable symptoms or suspected recurrence, they were encouraged to attend a clinical review.

Healing of the fistula was defined as the surgical incision healing with no secretions, and no existing fistula under endoanal ultrasonography. Recurrence of fistula was confirmed when a patient met at least one of the following criteria: (I) the surgical incision was unhealed after 3 months; (II) the surface of the incision was still producing secretions after 3 months; (III) fistula was indicated by endoanal ultrasonography; (IV) secondary surgery was required.

A visual analog scale (VAS) was used to evaluate postoperative pain, with a score ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (extremely severe pain). The severity of fecal incontinence was assessed using the Wexner Continence Grading Scale, which has five domains (solid, liquid, gas, pad wearing, and lifestyle alterations), with each domain scored from 0 (no incontinence) and 4 (severe incontinence).

The primary outcome in this study was the healing rate of fistula. Secondary outcomes included the recurrence rate of fistula and the severity of fecal incontinence.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline characteristics of patients. Median with interquartile range (IQR) was used for continuous variables (with non-normal distribution), and percentages were used for categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was employed to calculate the cumulative rates of healing and recurrence.

All statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Program for Social Sciences version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA). A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered to show statistical significance. Missing data of some variables were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Results

Baseline characteristics

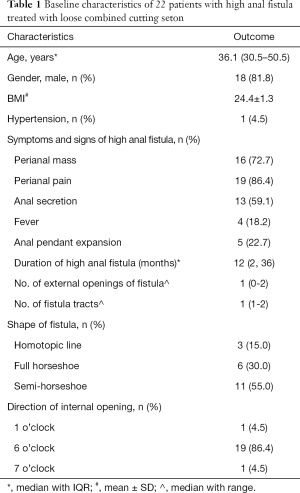

A total of 22 patients suffering from high anal fistula were eligible for inclusion. These patients had a median age of 36.1 years, and the majority (82%) were male. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 24.4, with a standard deviation of 1.3. One patient (4.5%) had hypertension; however, none of the other patients had any comorbidities. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the patients.

Full table

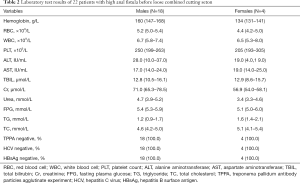

The median duration of high anal fistula was 12 months (IQR, 2–36 months). Symptoms among the patients included perianal pain (n=19), perianal mass (n=16), anal secretion (n=13), anal pendent expansion (n=5), and fever (n=4). Most patients had 1 fistula tract with 1 external opening. The internal opening was positioned in the 6 o’clock direction in 18 patients and the 7 o’clock direction in 1 patient, while 1 patient had 2 internal openings, at 1 and 6 o’clock respectively. In terms of shape, the fistulae were semi-horseshoe in 11 patients and full horseshoe in 6 patients, while 3 had a homotopic line. Table 2 shows the laboratory results of the patients before surgery. All patients had normal biochemistry indices.

Full table

Fistula healing and recurrence

LCCS was successfully performed on all patients. After the procedure, the patients were followed-up. The follow-up visits included anal inspection, digital anal examination, endoanal ultrasonography, and anorectal manometry. The median follow-up was 58 (IQR, 37–77; range, 32–568) days. The results of anal inspection revealed scarring in 1 patient; none of the patients showed malformation. No masses, induration, or tenderness were observed in any of the patients during digital anal examination. Fifteen patients underwent endoanal ultrasonography postoperatively; all of them were found to have normal endoanal hypoechogenicity.

As shown in Table 3, 17 patients underwent postoperative anorectal manometry. The mean values of anal resting pressure, maximum systolic pressure, and rectal anal pressure difference were 91.4, 188.7 and −32 mmHg, respectively. The mean length of the high-pressure zone was 3.9 cm. Recto-anal inhibitory reflex was observed in 14 patients (82.3%).

Full table

The mean time from seton insertion to complete healing (primary healing) was 40 (range, 30–50) days. The fistula healing rate was 100%, and none of the patients reported recurrence of fistula.

Incontinence

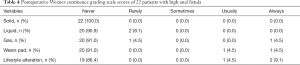

According to the Wexner Continence Grading Scale, a majority of the 22 patients did not present with any fecal incontinence at the follow-up visit. The median total Wexner score was 0 (range, 0–12). Two of patients reported experiencing liquid incontinence “rarely”, one patient reported “always” having gas incontinence, two patients “usually” needed to wear pads, and three patients reported lifestyle alterations. Additionally, two patients “usually” experienced anal itching (Table 4).

Full table

VAS score

At the postoperative follow-up visit, 21 patients had a VAS score of 0 and only 1 patient had a VAS score of 1, which indicated that LCCS resulted in a low level of postoperative pain.

Discussion

In the treatment of high anal fistula, curing the fistula while simultaneously avoiding sphincter damage presents a considerable challenge (5,9,21,22). Until now, none of the existing treatment methods could eliminate the fistula completely while maintaining continence. Our retrospective study is the first to demonstrate that LCCS, a novel seton-based technique that combines loose seton with cutting seton, could achieve a high healing rate with increased continence in the majority of patients, as well as a low level of postoperative pain. Additionally, at the end of follow-up (median, 58 days), none of the patients had experienced fistula recurrence.

LCCS combines the curative effect of cutting seton (5) with the drainage and anal protection offered by loose seton (23). In LCCS, silk thread seton is ligated on the fistula above the internal opening or infected space after the correct detection and disposal of the internal opening of the fistula; this is the same surgical procedure as that used with cutting seton. However, the seton is not tightened again when the ligation is loose. Thus, the loose seton can facilitate drainage and promote the development of a mature fistula track. When the granulation tissue filling in the fistula, the seton is removed. In this study, LCCS achieved a satisfactory effectiveness in a relatively short time (mean curing duration, 40 days) with incomplete cutting of the anorectal ring and the maintenance of continence, which is similar to the effects of loose seton after surgery.

This new technique has several strengths. Firstly, silk thread ligation can be used instead of rubber band (24,25). Silk thread has stronger cutting force with a more rapid cutting speed, which shortens the average operation time from 120 to 30 minutes. Meanwhile, silk thread can help to alleviate stimulation by foreign material, resulting in less pain during surgery. Moreover, as silk thread results in only mild damage to the anorectal ring, patients can quickly recover with little scarring. Furthermore, silk thread involves only a small area of the fistula tract in drainage removal, which can help to avoid infection recurrence.

Secondly, this treatment does not involve completely cutting the anorectal ring. In our study, we only partially cut the anorectal ring during surgery, with the complete removal of the internal opening of the anorectal ring and infected location. Furthermore, the seton was not tightened again on day 7 after surgery, which avoided the anorectal ring being completely cut through. Therefore, as well as curing the anal fistula, LCCS ensures that the normal contraction and release functions of the anal sphincter are protected and the patient’s continence can be maintained. Besides, with this technique, the postoperative pain caused by tightening of the seton can be avoided, with only a small postoperative scar and without anus deformation.

Thirdly, no additional dressing change is needed postoperatively. Necrotic infectious tissue can be replaced by fresh granulation through the drainage enabled by the loose silk thread, thus curing the fistula. Therefore, the patient’s pain can be alleviated and the economic burden due to dressing changes is reduced.

This study has some limitations that need to be noted. Firstly, this was a retrospective study and several measurements, including the Wexner Continence Grading Scale and VAS scores, are not required in routine clinical practice; as a result, some data were not collected preoperatively. Therefore, the effects of LCCS on incontinence and perianal pain before and after surgery could not be compared. Secondly, the follow-up period in our study was not long enough. While the longest follow-up was 568 days, the median follow-up was only 58 days; thus, the recurrence rate with LCCS may have been overestimated. Furthermore, there was only one group of patients in our study, with all subjects treated using the LCCS technique. Consequently, more randomized controlled trials with loose seton or cutting seton as a control are needed to validate the effectiveness of this novel seton-based technique in the future.

Conclusions

In summary, LCCS was shown to achieve a high healing rate with an increased level of continence in patients with high anal fistula, as well as a low level of postoperative pain. Further randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm the effectiveness of LCCS as a new seton-based technique.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Project of Wu Jieping Foundation: 320.6750.2020-8-34.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-6123

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-6123

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-6123). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by ethics committee of China-Japan Hospital (No.: 2019-SFZX-7). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient who agreed to participate in this study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zanotti C, Martinez-Puente C, Pascual I, et al. An assessment of the incidence of fistula-in-ano in four countries of the European Union. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:1459-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sneider EB, Maykel JA. Anal abscess and fistula. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2013;42:773-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amato A, Bottini C, De Nardi P, et al. Evaluation and management of perianal abscess and anal fistula: a consensus statement developed by the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR). Tech Coloproctol 2015;19:595-606. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, et al. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut 1999;44:77-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Subhas G, Singh Bhullar J, Al-Omari A, et al. Setons in the treatment of anal fistula: review of variations in materials and techniques. Dig Surg 2012;29:292-300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dudukgian H, Abcarian H. Why do we have so much trouble treating anal fistula? World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:3292-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sileri P, Cadeddu F, D'Ugo S, et al. Surgery for fistula-in-ano in a specialist colorectal unit: a critical appraisal. BMC Gastroenterol 2011;11:120. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan KK, Alsuwaigh R, Tan AM, et al. To LIFT or to flap? Which surgery to perform following seton insertion for high anal fistula? Dis Colon Rectum 2012;55:1273-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitalas LE, van Wijk JJ, Gosselink MP, et al. Seton drainage prior to transanal advancement flap repair: useful or not? Int J Colorectal Dis 2010;25:1499-502. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Theerapol A, So BY, Ngoi SS. Routine use of setons for the treatment of anal fistulae. Singapore Med J 2002;43:305-7. [PubMed]

- Mentes BB, Oktemer S, Tezcaner T, et al. Elastic one-stage cutting seton for the treatment of high anal fistulas: preliminary results. Tech Coloproctol 2004;8:159-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eitan A, Koliada M, Bickel A. The use of the loose seton technique as a definitive treatment for recurrent and persistent high trans-sphincteric anal fistulas: a long-term outcome. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:1116-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faucheron JL, Saint-Marc O, Guibert L, et al. Long-term seton drainage for high anal fistulas in Crohn's disease--a sphincter-saving operation? Dis Colon Rectum 1996;39:208-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chuang-Wei C, Chang-Chieh W, Cheng-Wen H, et al. Cutting seton for complex anal fistulas. Surgeon 2008;6:185-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zbar AP, Ramesh J, Beer-Gabel M, et al. Conventional cutting vs. internal anal sphincter-preserving seton for high trans-sphincteric fistula: a prospective randomized manometric and clinical trial. Tech Coloproctol 2003;7:89-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balogh G. Tube loop (seton) drainage treatment of recurrent extrasphincteric perianal fistulae. Am J Surg 1999;177:147-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi D, Sung Kim H, Seo HI, et al. Patient-performed seton irrigation for the treatment of deep horseshoe fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:812-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Subhas G, Gupta A, Balaraman S, et al. Non-cutting setons for progressive migration of complex fistula tracts: a new spin on an old technique. Int J Colorectal Dis 2011;26:793-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patton V, Chen CM, Lubowski D. Long-term results of the cutting seton for high anal fistula. ANZ J Surg 2015;85:720-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- García-Aguilar J, Belmonte C, Wong DW, et al. Cutting seton versus two-stage seton fistulotomy in the surgical management of high anal fistula. Br J Surg 1998;85:243-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shawki S, Wexner SD. Idiopathic fistula-in-ano. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:3277-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garg PK, Jain BK. Seton drainage in high anal fistula. Int J Colorectal Dis 2011;26:1495. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelly ME, Heneghan HM, McDermott FD, et al. The role of loose seton in the management of anal fistula: a multicenter study of 200 patients. Tech Coloproctol 2014;18:915-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Awad ML, Sell HW, Stahlfeld KR. Split-shot sinker facilitates seton treatment of anal fistulae. Colorectal Dis 2009;11:524-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takesue Y, Ohge H, Yokoyama T, et al. Long-term results of seton drainage on complex anal fistulae in patients with Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol 2002;37:912-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editor: J. Reynolds)