Quadriceps tendinopathy: a review, part 2—classification, prognosis, and treatment

Current classification systems

The main symptom of quadriceps tendinopathy is anterior knee pain, with varying intensity levels located within various areas of the extensor mechanism apparatus. Patients often complain of gradual worsening of pain which is related to activity, and often do not recall or describe an inciting event (1). The most common location is the origin of the patellar tendon (65% to 70% of the cases), followed by the insertion of the quadriceps tendon at the superior pole of the patella (20% to 25%), and the patellar tendon insertion on the tibial tuberosity (5% to 10%). The classification proposed by Blazina et al. (2) and Roels et al. (3) is based on the effects of pain and sports performance, however, a more recent classification by Ferretti et al. (4) is based on the intensity of pain.

The Blazina classification consists of:

- Pain after activity only without functional impairment;

- Pain during and after activity with satisfactory performance levels;

- Pain during and after activity more prolonged with progressively increasing difficulty performing at a satisfactory level.

The classification by Roels et al. modified the Blazina classification scheme to include tendon rupture:

- Pain at the infrapatellar or suprapatellar region after practice or event;

- Pain at beginning of activity, disappearing after warming up and reappearing after completion of activity;

- Pain remains during and after activity and the patient is unable to participate in sports;

- Represents a complete rupture of the tendon.

Ferretti et al. modified Blazina’s classification based on the intensity of pain:

- Stage 0: no pain;

- Stage 1: pain only after intense sports activity with no functional impairment;

- Stage 2: moderate pain during sports activity with no restriction on sports performance;

- Stage 3: pain with slight restriction on performance;

- Stage 4: pain with severe restriction of sports performance;

- Stage 5: pain during daily activity and unable to participate in sport at any level.

To date, there is no tendinopathy classification scheme to diagnose and guide treatment protocols based on the wide pathologic tendon features rather than symptoms based alone. This highlights the importance of further studies that are needed to assist in the management of tendinopathy in clinical practice.

Prognosis and treatment

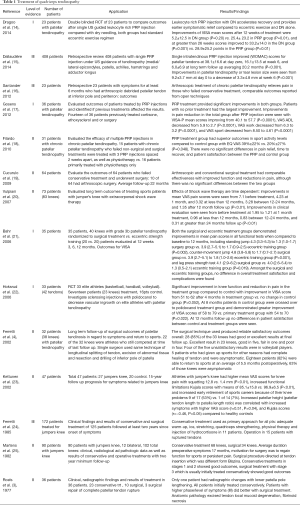

Historically, the management of quadriceps tendinopathy is based on the classifications by Blazina, Roels et al., and Ferretti et al., which correlated the treatment based on the stage of patient symptoms. It is most commonly treated non-operatively with rest, activity modification, ultrasound, and physical therapy with eccentric training programs (5-13) (Table 1). However, among patients with severe tendinosis who fail non-operative treatments, the options of injections are also available. Patients with severe quadriceps tendinopathy are at increased risk for tendon rupture without treatment (26). A prospective study of 20 athletes with quadriceps tendinopathy were followed for 15 years by Kettunen et al. (23), found that compared to healthy controls, athletes with quadriceps tendinopathy had higher mean visual analog scale scores for knee pain with squatting (12.8 vs. 1.4; P<0.01), increased functional limitations measured by Kujala score (27) with means of 85.1 vs. 97 points (P<0.01), and increased early retirement of their sports careers because of their knee problems 9 (53%) vs. 1 (7%).

Full table

In the early stages of quadriceps tendinopathy described by Blazina et al. (2) and modified by Roels et al. (3) non-operative treatment is often successful at providing symptomatic relief (11,20,25). A retrospective study of 172 athletes with patellar tendinopathy (110 who remained in sport) by Ferretti et al. (4) evaluated the outcomes of non-operative and surgical treatment in the various Blazina stages. The prevalence of different stages in the study included 24 (21.8%) stage 1, 42 (38.1%) stage 2, 43 (29.1%) stage 3, and 1 (1%) stage 4. Among the athletes being treated, localized pain was found at lower pole of the patella in 71 (64.5%), at the insertion of quadriceps tendon in 27 (25%), and at the tibial tuberosity in 11 (10%). The overall results obtained from the study was classified into the following groups.

- Very good: no pain, tenderness, muscle wasting or limitation of activities.

- Good: mild pain during vigorous sport but no restriction, slight tenderness, and moderate muscle wasting.

- Poor: moderate to severe pain after a long period of sitting and during sport, limitation of activity, moderate to severe tenderness and severe quadriceps muscle wasting.

According to the groups that were classified, they found non-operative treatment used on all patients had good outcomes in those with early stages of the disease. Non-operative treatment without rest or reduction of sports activity was used in 81 athletes, the outcomes of those in the first and second stage included very good in 16 (38%), good in 10 (24%), and poor in 16 (38%) compared to the outcomes of those in the third stage included 4 (10%) very good, 8 (20%) good, and 27 (69%) poor of which 15 of the 27 were operated on later. In 36 cases, the addition of a long period of rest and reduction of sporting activity was added to the treatment, and was found to be beneficial in all stages, especially for those in the later stages. A total of 16 patients (19 knees) with stage 3 or 4 underwent surgical treatment which resulted in 7 (38%) very good, 5 (26%) good, and 7 (38%) poor outcomes.

Multiple studies have evaluated the use of injections such as platelet rich plasma (PRP), and sclerosing agents such as polidocanol. Both of these may be viable treatment options and provide symptomatic relief in certain cases of tendinopathy (17,28). A randomized controlled trial of 23 patients with patellar tendinopathy by Dragoo et al. (14) compared patients who were undergoing eccentric training, and compared outcomes of the addition of leukocyte-rich PRP injection with dry needling. They found that the addition of a leukocyte rich PRP injection with dry needling provided earlier symptomatic relief compared to eccentric exercise and dry needling alone. After 12 weeks of treatment, only the PRP group demonstrated statistically significant improvements in pain and function compared to dry needling. At 26 weeks, both groups had clinical improvements, however, the differences between the groups was not statistically significant.

A retrospective review of 408 patients who had tendinopathy of the upper or lower limbs treated by a single US-guided PRP injection by Dallaudière et al. (15) demonstrated increased rapid tendon healing, satisfactory patient tolerance, as well as improvements in patellar tendinopathy tear lesion size (9.2 mm at day 0 to 3.3 mm at week 6, P<0.001). Filardo et al. (18) evaluated the efficacy of multiple PRP injections in 31 patients with chronic grade III Blazina (29) patellar tendinopathy who failed conservative treatment for a minimum of 2 months compared with physiotherapy alone (15 PRP, 16 control physiotherapy). At 6-month follow-up the PRP treatment group had greater improvements in post-treatment sport activity levels compared to the control group (39% vs. 20%, P=0.048), with mean Tegner (30) scores of 6.6 from 3.7 for PRP (P=0.001) vs. 6.8 from 5.3 for controls (P=0.0005). These results demonstrate that PRP injections can improve clinical outcomes in refractory cases of patellar tendinopathy.

A randomized controlled trial of 33 patients (42 tendons), who had chronic patellar tendinopathy by Hoksrud et al. (22) compared outcomes with treatment of sclerosing injections of polidocanol compared with controls using lidocaine/epinephrine [17 patients (22 knees) were included in the treatment group vs. 16 patients (20 knees) in the control group]. They found significant improvements in knee function and reduction in pain in the polidocanol group compared to control with improvement in mean VISA (31) scores from 51 to 62 after 4 months in the polidocanol group vs. no change in control group (P=0.052). At 8 months, patients in the lidocaine/epinephrine control group received polidocanol treatment and demonstrated greater improvement in mean VISA scores compared to the primary polidocanol treatment group at 58 to 79 vs. 54 to 70 points (P=0.022). At 12 months follow up, no differences in patient satisfaction between the lidocaine/epinephrine control and polidocanol treatment groups were seen.

Surgical treatment

Several studies have evaluated the surgical treatment of athletes who had tendinopathy and have shown superior outcomes in patients who have failed non-operative treatments for a minimum of 3 months (4,16,25). Various surgical techniques for treatment of patellar tendinopathy have been described in the literature, however, a consensus for the best surgical treatment option still does not exist (32-38). A retrospective study by Cucurulo et al. (19) examined outcomes of 64 athletes who had patellar tendinopathy treated by arthroscopic or conventional open surgery after failing non-operative treatment that averaged 28 months. Both arthroscopic and conventional surgical treatments provided symptomatic relief of activity related knee pain classified by Blazina et al. (2) when compared to the preoperative levels, however, differences between the two surgical techniques were not statistically significant. A randomized controlled trial by Willberg et al. (39) compared the clinical outcomes of 45 patients (52 knees) with patellar tendinopathy treated by either sclerosing polidocanol injections or arthroscopic shaving, both treatments utilized ultrasound plus color Doppler. Compared to the polidocanol injection group, the arthroscopic treatment group had significant improvements in mean VAS scores for pain at rest (5 vs. 19, P=0.004), pain with activity (12 vs. 41, P=0.001) as well as increased patient satisfaction. A similar study by Alfredson et al. (40) evaluated treatment consisting of ultrasound and Doppler guided arthroscopic shaving with open scraping followed by immediate weight bearing on 9 professional rugby players with patellar tendinopathy. They achieved good clinical results with increased mean VISA scores at 78 from 49 at baseline (P<0.05), and 7 out of the 9 players returned to play full professional rugby within 4 to 6 months. The two players who could not return to sport due to poor clinical outcomes had previous tendon revision surgeries.

A prospective study of 32 athletes, who had patellar tendinopathy by Ferretti et al. (4) evaluated long-term surgical outcomes according to symptoms and return to sport with a minimum of five years follow-up. Using a modified Blazina classification (2), as previously described, they grouped the results at the final follow-up into stages.

- Excellent: when patient was at stage 0 at the final follow-up.

- Good: when patient was at stage 1 with postoperative improvement of at least two stages.

- Fair: when improvement occurred but the final result was stage 2 or higher.

- Poor: no improvement occurred.

According to the grouped stages, satisfactory results were obtained for their technique of longitudinal splitting of the tendon, excision of abnormal tissue, and resection and drilling of the inferior pole of the patella. At final follow up, good or excellent results were seen in 28 (85%) knees, excellent in 23 (71%), good in 5 (16%), fair in 1 (3%), and poor in 4 (13%), while 80% of the unsatisfactory results were in volleyball players. Eighteen patients (82%) were able to return to sports at a mean of approximately 6 months postoperatively, of those, 11 (63%) were asymptomatic.

In summary, there are multiple treatment modalities for quadriceps tendinopathy. Non-operative measures have shown good outcomes in the early stages of tendinopathy. Injections of PRP and sclerosing agents such as polidocanol may provide symptomatic relief in those who have failed first line non-operative measures and are alternative treatment options. Surgical treatment for quadriceps tendinopathy should be reserved for those who are in the later stages of tendinopathy, and those who have exhausted non-operative treatments. Arthroscopic and open surgical treatments have shown superior outcomes in advanced stage tendinopathy compared to non-operative treatments. The outcomes of surgical treatment of quadriceps tendinopathy have been studied extensively in athletes, however, there is a need for additional studies in the non-athlete population.

Discussion/conclusions

Quadriceps tendinopathy is an important cause of anterior knee pain. It is a clinical diagnosis characterized by activity-related anterior knee pain and is most commonly seen with overuse activities in athletes. Structural histologic tendon changes found in quadriceps tendinopathy have consistently demonstrated more degenerative rather than inflammatory changes. The use of conventional diagnostic imaging for quadriceps tendinopathy diagnosis reveals morphologic changes of localized tendon thickening, hypoechoic areas, and increased vascularity. Quadriceps tendinopathy is initially managed non-operatively with rest, ice, proper warm-up, and physical therapy. Injections of PRP and sclerosing agents such as polidocanol have shown good outcomes in patients with patellar tendinopathy who have failed non-operative treatment. Arthroscopic and open surgical procedures have shown good outcomes in patients with severe symptoms who have failed non-operative treatment. More recently, an association has been found between non-athletic patients who have a high BMI and patellar tendinopathy. These findings highlight the importance in surveillance of quadriceps tendinopathy as a cause of anterior knee pain in non-athletes. In addition, the development of an ultrasound classification scheme for the management of tendinopathy based on pathologic tendon changes rather than just symptomology alone would prove invaluable for clinical practice, however, there is a need for additional validation studies.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: M Chughtai: Cymedica; DJ Orthopaedics; Peerwell; Performance Dynamics Inc.; Refelection; Sage Products; Stryker. P Saluan: AAOS Now; Arthrex, Inc.; Equalizer, LLC; Middle Path Innovations, LLC; Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America. MA Mont: AAOS, Cymedica, DJ Orthopaedics, Johnson & Johnson, Journal of Arthroplasty, Journal of Knee Surgery, Microport, National Institutes of Health (NIAMS & NICHD), Ongoing Care Solutions, Orthopedics, Orthosensor, Pacira, Peerwell, Performance Dynamics Inc., Sage, Stryker: IP royalties, Surgical Technologies International, Kolon TissueGene. J Genin: Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Goldin M, Malanga GA. Tendinopathy: a review of the pathophysiology and evidence for treatment. Phys Sportsmed 2013;41:36-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blazina ME, Kerlan RK, Jobe FW, et al. Jumper’s knee. Orthop Clin North Am 1973;4:665-78. [PubMed]

- Roels J, Martens M, Mulier JC, et al. Patellar tendinitis (jumper’s knee). Am J Sports Med 1978;6:362-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferretti A, Conteduca F, Camerucci E, et al. Patellar tendinosis: a follow-up study of surgical treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84-A:2179-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scattone Silva R, Nakagawa TH, Ferreira AL, et al. Lower limb strength and flexibility in athletes with and without patellar tendinopathy. Phys Ther Sport 2016;20:19-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rudavsky A, Cook J. Physiotherapy management of patellar tendinopathy (jumper’s knee). J Physiother 2014;60:122-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Larsson MEH, Käll I, Nilsson-Helander K. Treatment of patellar tendinopathy—a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012;20:1632-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Visnes H, Bahr R. The evolution of eccentric training as treatment for patellar tendinopathy (jumper’s knee): a critical review of exercise programmes. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:217-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Figueroa D, Figueroa F, Calvo R. Patellar Tendinopathy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2016;24:e184-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Merchan EC. The treatment of patellar tendinopathy. J Orthop Traumatol 2013;14:77-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jonsson P, Alfredson H. Superior results with eccentric compared to concentric quadriceps training in patients with jumper’s knee: a prospective randomised study. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:847-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woodley BL, Newsham-West RJ, Baxter GD. Chronic tendinopathy: effectiveness of eccentric exercise. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:188-98; discussion 199. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rio E, Kidgell D, Purdam C, et al. Isometric exercise induces analgesia and reduces inhibition in patellar tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1277-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dragoo JL, Wasterlain AS, Braun HJ, et al. Platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for patellar tendinopathy: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:610-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dallaudière B, Pesquer L, Meyer P, et al. Intratendinous injection of platelet-rich plasma under US guidance to treat tendinopathy: A long-term pilot study. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014;25:717-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santander J, Zarba E, Iraporda H, et al. Can arthroscopically assisted treatment of chronic patellar tendinopathy reduce pain and restore function? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:993-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gosens T, Den Oudsten BL, Fievez E, et al. Pain and activity levels before and after platelet-rich plasma injection treatment of patellar tendinopathy: A prospective cohort study and the influence of previous treatments. Int Orthop 2012;36:1941-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Filardo G, Kon E, Della Villa S, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of refractory jumper’s knee. Int Orthop 2010;34:909-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cucurulo T, Louis ML, Thaunat M, et al. Surgical treatment of patellar tendinopathy in athletes. A retrospective multicentric study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2009;95:S78-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vulpiani MC, Vetrano M, Savoia V, et al. Jumper's knee treatment with extracorporeal shock wave therapy: a long-term follow-up observational study. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2007;47:323-8. [PubMed]

- Bahr R, Fossan B, Løken S, et al. Surgical Treatment Compared with Eccentric Training for Patellar Tendinopathy (Jumper’s Knee). J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:1689-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoksrud A, Ohberg L, Alfredson H, et al. Ultrasound-Guided Sclerosis of Neovessels in Painful Chronic Patellar Tendinopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Sports Med 2006;34:1738-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kettunen JA, Kvist M, Alanen E, et al. Long-term prognosis for jumper’s knee in male athletes. A prospective follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:689-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferretti A, Puddu G, Mariani PP, et al. The natural history of jumper's knee. Patellar or quadriceps tendonitis. Int Orthop 1985;8:239-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martens M, Wouters P, Burssens A, et al. Patellar tendinitis: pathology and results of treatment. Acta Orthop Scand 1982;53:445-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelly DW, Carter VS, Jobe FW, et al. Patellar and quadriceps tendon ruptures--jumper’s knee. Am J Sports Med 1984;12:375-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kujala UM, Jaakkola LH, Koskinen SK, et al. Scoring of patellofemoral disorders. Arthroscopy 1993;9:159-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Charousset C, Zaoui A, Bellaiche L, et al. Are Multiple Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections Useful for Treatment of Chronic Patellar Tendinopathy in Athletes? A Prospective Study. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:906-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blazina ME, Kerlan RK, Jobe FW, et al. Jumper’s knee. Orthop Clin North Am 1973;4:665-78. [PubMed]

- Tegner Y, Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1985.43-9. [PubMed]

- Visentini PJ, Khan KM, Cook JL, et al. The VISA score: an index of severity of symptoms in patients with jumper’s knee (patellar tendinosis). Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. J Sci Med Sport 1998;1:22-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stuhlman CR, Stowers K, Stowers L, et al. Current Concepts and the Role of Surgery in the Treatment of Jumper’s Knee. Orthopedics 2016;39:e1028-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ogon P, Maier D, Jaeger A, et al. Arthroscopic Patellar Release for the Treatment of Chronic Patellar Tendinopathy. Arthroscopy 2006;22:462.e1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maier D, Bornebusch L, Salzmann GM, et al. Mid- and long-term efficacy of the arthroscopic patellar release for treatment of patellar tendinopathy unresponsive to nonoperative management. Arthroscopy 2013;29:1338-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lorbach O, Diamantopoulos A, Paessler HH. Arthroscopic Resection of the Lower Patellar Pole in Patients With Chronic Patellar Tendinosis. Arthroscopy 2008;24:167-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brockmeyer M, Diehl N, Schmitt C, et al. Tendinosis (Jumper ’ s Knee): A Systematic Review of the Literature. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg 2015;31:2424-9.e3. [Crossref]

- Brockmeyer M, Haupert A, Kohn D, et al. Surgical Technique: Jumper’s Knee—Arthroscopic Treatment of Chronic Tendinosis of the Patellar Tendon. Arthrosc Tech 2016;5:e1419-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sunding K, Willberg L, Werner S, et al. Sclerosing injections and ultrasound-guided arthroscopic shaving for patellar tendinopathy: good clinical results and decreased tendon thickness after surgery—a medium-term follow-up study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:2259-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Willberg L, Sunding K, Forssblad M, et al. Sclerosing polidocanol injections or arthroscopic shaving to treat patellar tendinopathy/jumper’s knee? A randomised controlled study. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:411-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alfredson H, Masci LA, Alfredson H, et al. Ultrasound and Doppler-Guided Surgery for the Treatment of Jumper’s Knee in Professional Rugby Players. Pain Stud Treat 2015;3:1-5. [Crossref]