Prevalence of diabetic foot ulceration and associated risk factors: an old and still major public health problem in Khartoum, Sudan?

Introduction

Diabetes is now common and major health problem in Sudan. The estimated prevalence of diabetes in urban areas in North Sudan was thought to be around 19% in comparison with 2.5% in rural regions (1,2). Like other developed and developing countries, high prevalence of uncontrolled diabetes (85%) is noted in Sudanese individuals with type 2 diabetes (3). Therefore, it is not surprising that the prevalence of fatty liver among Sudanese individuals with type 2 diabetes was found to be as high as 50.3% (4). Importantly, Increasing age, a family history of diabetes, central obesity, obesity, an increase in metabolic syndrome parameters, hypertension and high triglyceride level and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) level were significant risk factors for both diabetes and fatty liver in Sudanese individuals (1-4). Unfortunately, the prevalence of diabetes in Africa is expected to increase to 28 million cases by 2030 in comparison with 14 million in 2011 (5-7). In systematic review, the global diabetic foot ulcer prevalence was 6.3% (highest in North America about 13%, lowest in Europe about 3% and Africa about 7.2%). Diabetic foot ulceration (DFU) was noted more in males, type 2 diabetics, older individuals, low body mass index (BMI), longer diabetic duration, hypertension, diabetic retinopathy (DR), and smoking history than in patients without DFU (8). Increase in prevalence of diabetes complications in Africa was attributed to rise in financial health expenditure, poor medical facility and lack of adequate diabetes service in urban and rural areas (9,10). The prevalence of diabetic foot in Cameroon, Nigeria and Tanzania were estimated to be 13%, 9.5% and 15% respectively (11-13). The cost associated with diabetic foot is enormous. For instance, the costs of treatment for diabetic foot that resulted in complete healing ranged from $102 to $3959 in Tanzania and in the United States, respectively. Importantly, the cost of diabetic foot that treated with transtibial amputation ranged from $3,060 to $188,645 in Tanzania and in the United States, respectively. On the other hand, the cost burden to the patient varied from the equivalent of 6 days of average income in the United States for diabetic foot with complete recovery to 5.7 years of average annual income in case of transtibial amputation in India (14). In addition, 28% to 51% of amputated diabetics will have a second amputation of the lower limb within five years of the first amputation. This was thought to be due to neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, poor diabetes control and longer duration of diabetes (8,15). Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine the prevalence of diabetic foot in Sudanese individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Study design

This was a descriptive, cross sectional, hospital-based study.

Setting and population

Individuals with diabetes who attended diabetes center in the capital of Sudan, Khartoum were included in this study.

Inclusion criteria

Included adults over 18 years who were diagnosed as type 2 diabetes, individuals with diabetes on diet control, individuals with macro-micro diabetes complications were included and being on anti-diabetes treatment for at least 1 year.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included: individuals below 18 years, individuals admitted with diabetes emergencies like diabetic ketoacidosis and pregnant ladies.

Data collection tools

A validated, pre-tested, interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to obtain demographic data, diabetes related enquiries in addition to physical measurements including anthropometric measurements and biochemical tests. Questions related to diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), DR, diabetic foot and cardiovascular complications were included. Lipid profile and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) were tested by calibrated laboratory methods. Blood pressure, BMI and waist circumference were measured as these are indirectly related to complications of diabetes mellitus.

Laboratory methods

Fasting levels of plasma glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL) and HbA1c were measured using standardized laboratory techniques.

Ethical clearance

A written consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment. The following information was given during data collection, to insure that participants had the information needed to make the informed consent. Furthermore, participation was optional and no penalty for refusal. A complete description of the aims of the study, potential benefits and risks, and assurance of confidentiality of any information given, any other additional information requested by participants was provided during data collection. A formal ethical approval was obtained from the ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Science and Technology in Khartoum (IRB No. 00008867).

Statistical analysis

Data had been collected, organized, coded and entered in master sheet in a personal computer and analysed using R statistical software version 3.1.2 and the Statistical Package for Social Science SPSS software program [version 21.0 computer program (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)].The main variables analyzed were age, sex, BMI, blood glucose level, retinopathy, neuropathy, albuminuria, blood pressure and a family history of diabetes mellitus, duration of diabetes, cholesterol, triglyceride and HbA1c. ANOVA test was used to test for significance between proportions. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Logistic regression analysis was used to establish absolute risk factors and to adjust for demographic and clinical variables.

Results

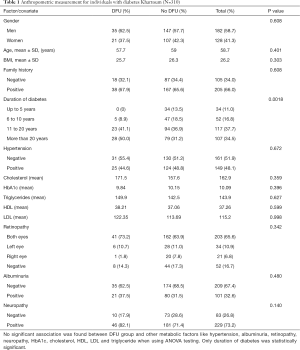

In this study, 310 individuals with type 2 diabetes were included. Their mean age was 58.7 years old. Males were 182 (58.7%) and females were 128 (41.3%). The prevalence of diabetic foot was found to be 18.1% in this cohort (95% CI: 13.78–22.34%).The mean BMI was 26.2 m2/kg. The presence of hypertension, nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy were found not to be associated with diabetic foot with P value (0.62, 0.34, 0.48 and 0.14) respectively. HbA1c, cholesterol, HDL, LDL and Triglyceride were also not statistically associated with diabetic foot with P value of (0.39, 0.35, 0.59, 0.99 and 0.62) respectively. Duration of diabetes was significantly associated with DFU (P<0.0018) (Table1).

Full table

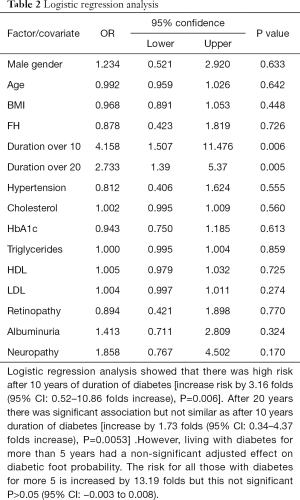

Logistic regression to identify absolute predictors of diabetic foot

We conducted stepwise logistic regression for all the variables that were deemed clinically significant (Table 1) in order to identify absolute predictors of DFU. Utilizing the full logistic regression model that adjusts for all risk factors for diabetic foot simultaneously, only the duration of DM was the statistically significant. Even after adjusting for all other potential risk factors, living with diabetes for more than 10 years is associated with an increase in the diabetic foot probability by 3.16 folds (95% CI: 0.52–10.86 folds increase), P=0.006. The adjusted effect for living with diabetes for more than 20 years on the diabetic foot complication probability is an increase by 1.73 folds (95% CI: 0.34–4.37 folds increase), P=0.0053. However, living with diabetes for more than 5 years had a non-significant adjusted effect on diabetic foot probability. The risk is increased by 13.19 folds but this not significant P>0.05 (95% CI: −0.003 to 0.008) (Table 2).

Full table

Discussion

The global prevalence was estimated to be 6.3% and in Africa it was estimated to be around 7.2% (8). In this study we have shown that the prevalence of diabetic foot is around 18.1% which is higher than the estimated prevalence regionally and internationally. For example the prevalence of diabetic foot in Cameroon, Nigeria and Tanzania were estimated to be 13%, 9.5% and 15% respectively (11-13). There is very limited research about prevalence of DFU in Sudan and to our knowledge this represents the first study about prevalence of diabetic foot. The DFU is characterized by infection, ulceration, peripheral neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease (16). The prevalence of neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease in Sudan was well documented in the literature. For instance, the prevalence of peripheral neuropathy in Sudan in association with diabetes showed progressive increase over the last 2 decades, as the prevalence in 1989 was 28.1%, in 1991 was 31.5%, 1995 it was 37% and in 2000 it was 66% (17-20). Importantly, this was attributed to prolonged duration of diabetes and poor glycemic control (17). In Tanzania it was noted that 100% of patients who presented with foot ulcers to a large diabetes outpatient clinic, had varying degrees of severity of peripheral neuropathy (13). In this study the prevalence of neuropathy in association with diabetic foot was 82.1%, this was not statistically significant as the prevalence of neuropathy in non DFU group was 71.4%. This could be alarming, as this may suggest that there is high potential risk of developing DFU in the non DFU group. This may also explain why no significant association was found between DFU group and other metabolic factors like hypertension, nephropathy, retinopathy, neuropathy, HbA1c, cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglyceride. This due to the fact, that these variables are present in high levels in non-diabetic ulcer foot group. Several studies have shown association between diabetic foot and hypertension, albuminuria, retinopathy, neuropathy, HbA1c, cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglyceride (8,11-16). Peripheral vascular disease is another important contributor in pathogenesis of diabetic foot, and prevalence of peripheral vascular disease in Sudan in 1989 was estimated to be 6.2% and this increased to 10% in 1995 (18,20). Due to increase in urbanization across Africa there is an increase in prevalence of peripheral vascular disease. For instance, the prevalence of peripheral vascular disease in Nigeria was estimated to be 54% and in Tanzania was estimated to be 21% (13,21).

Importantly, only the duration of DM was the statistically significant risk factor. There was high risk after 10 years of duration of diabetes [increase risk by 3.16 folds (95% CI: 0.52–10.86 folds increase), P=0.006]. After 20 years there was significant association but not similar as after 10 years duration of diabetes [increase by 1.73 folds (95% CI: 0.34–4.37 folds increase), P=0.0053] .However, living with diabetes for more than 5 years had a non-significant adjusted effect on diabetic foot probability. The risk for all those with diabetes for more than 5 is increased by 13.19 folds but this not significant P>0.05 (95% CI: −0.003 to 0.008). Gumaa et al. showed that having diabetes for longer than 10 years was significant risk factors for development of diabetic foot in Sudanese individuals with diabetes (22). Malik et al. mentioned that ulceration, previous amputation, prolonged diabetes duration and poor long-term control of glycaemia and lipids are important risk factors for amputation in populations with diabetes (23).

In systemic review by international research collaboration for the prediction of diabetic foot ulcerations (PODUS), they showed that inability to feel a 10 g monofilament (OR =3.184; 95% CI: 2.654–3.82), at least one absent pedal pulse (OR =1.968; 95% CI: 1.624–2.386), a longer duration of a diagnosis of diabetes (OR =1.024; 95% CI: 1.011–1.036) and a previous history of ulceration (OR =6.589; 95% CI: 2.488–17.45) were all predictive of risk of diabetic foot. Interestingly, the authors of this report commented that the results in the validation data set for duration of diabetes were unexpected, where a longer duration of diabetes was protective against ulceration (24). This may explain the decrease in odd ratio in our study when the duration of diabetes was 20 years or more in comparison with odd ratio for 10 years. In another meta-analysis it was shown that age, gender, diabetes duration, BMI, HbA1c and neuropathy are associated with DFU. Diabetic neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, foot deformity and previous DFU or lower extremity amputation were consistently associated with DFU development (25). Further research is needed to assess whether tropical disease like mycetoma and leishmaniasis may have impact in development of DFU in Sudan.

This study is not without limitations. The study design was a cross-sectional study, so we could not take account of the temporal relationship between potential risk factors and outcomes. Another limitation is the short duration of the study and we are not able to assess for late diagnosis of diabetes. Despite these factors, we believe that this study is novel and its findings reflect the trend of rising frequency of DFU in developing countries.

Conclusions

Prevalence of diabetic foot ulcer among individuals with type 2 DM was 18.1%, which is higher when compared with regional and global figures, as well the DFU was significantly associated with duration of diabetes for at least 10 years.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Health Insurance Corporation, Khartoum State (HIKS), Sudan.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the ethnical committee in University Medical and Science and Technology (UMST), Khartoum, Sudan (IRB No. 00008867). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

References

- Elmadhoun WM, Noor SK, Ibrahim AA, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in urban communities of north Sudan: Population-based study. J Diabetes 2016;8:839-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noor SK, Bushara SO, Sulaiman AA, et al. Undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in rural communities in Sudan: prevalence and risk factors. East Mediterr Health J 2015;21:164-70. [PubMed]

- Noor SK, Elmadhoun WM, Bushara SO, et al. Glycaemic control in Sudanese individuals with type 2 diabetes: Population based study. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Almobarak AO, Barakat S, Suliman EA, et al. Prevalence of and predictive factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Sudanese individuals with type 2 diabetes: Is metabolic syndrome the culprit? Arab J Gastroenterol 2015;16:54-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 5th. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2011.

- Hall V, Thomsen RW, Henriksen O, et al. Diabetes in Sub Saharan Africa 1999-2011: epidemiology and public health implications. A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2011;11:564. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Dieren S, Beulens JW, van der Schouw YT, et al. The global burden of diabetes and its complications: an emerging pandemic. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17 Suppl 1:S3-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang P, Lu J, Jing Y, et al. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med 2017;49:106-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elrayah H, Eltom M, Bedri A, et al. Economic burden on families of childhood type 1 diabetes in urban Sudan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005;70:159-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bos M, Agyemang C. Prevalence and complications of diabetes mellitus in Northern Africa, a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013;13:387. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kengne AP, Djouogo CF, Dehayem MY, et al. Admission trends over 8 years for diabetic foot ulceration in a specialized diabetes unit in cameroon. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2009;8:180-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ogbera AO, Fasanmade O, Ohwovoriole AE, et al. An assessment of the disease burden of foot ulcers in patients with diabetes mellitus attending a teaching hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2006;5:244-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gulam-Abbas Z, Lutale JK, Morbach S, et al. Clinical outcome of diabetes patients hospitalized with foot ulcers, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Diabet Med 2002;19:575-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh P, Attinger C, Abbas Z, et al. Cost of treating diabetic foot ulcers in five different countries. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2012;28 Suppl 1:107-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Diouri A, Slaoui Z, Chadli A, et al. Incidence of factors favoring recurrent foot ulcers in diabetic patients. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2002;63:491-6. [PubMed]

- Abbas ZG, Archibald LK. Epidemiology of the diabetic foot in Africa. Med Sci Monit 2005;11:RA262-70. [PubMed]

- Ahmed AM, Hussein A, Ahmed NH. Diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Saudi Med J 2000;21:1034-7. [PubMed]

- el Mahdi EM, Abdel Rahman Iel M, Mukhtar Sel D. Pattern of diabetes mellitus in the Sudan. Trop Geogr Med 1989;41:353-7. [PubMed]

- Elmahdi EM, Kaballo AM, Mukhtar EA. Features of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) in the Sudan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1991;11:59-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elbagir MN, Eltom MA, Mahadi EO, et al. Pattern of long-term complications in Sudanese insulin-treated diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1995;30:59-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akanji AO, Adetuyidi A. The pattern of presentation of foot lesions in Nigerian diabetic patients. West Afr J Med 1990;9:1-5. [PubMed]

- Gumaa MM, Shwaib HM, Ali SM. Diabetic foot lesions predicting factors, view from Jabir Abu-alaiz diabetic centre in Khartoum, Sudan. The Journal of Diabetic Foot Complications 2016;8:6-17.

- Malik RA, Tesfaye S, Ziegler D. Medical strategies to reduce amputation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2013;30:893-900. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crawford F, Cezard G, Chappell FM, et al. A systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of prognostic factors for foot ulceration in people with diabetes: the international research collaboration for the prediction of diabetic foot ulcerations (PODUS). Health Technol Assess 2015;19:1-210. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monteiro-Soares M, Boyko EJ, Ribeiro J, et al. Predictive factors for diabetic foot ulceration: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2012;28:574-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]