Where do I see minimally invasive endoscopy in 2020: clock is ticking

Introduction

In late 1998 Gabriel Meron, the CEO of a small Israeli company named Given Imaging, travelled around the country introducing a concept a wireless capsule travelling along the small bowel and transmitting pictures of small bowel mucosa. Many of the listeners laughed within themselves, others were enthusiastic. The small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) was introduced in 2000 by its inventor—Dr. Iddan (1), and the rest is history. SBCE became an important if not the most important investigational tool for the small bowel.

Over 2,000 studies have been published since it is in the market, looking at its efficacy versus other modalities in various indications.

The present article focuses on the Medtronic (Given Imaging) platform on which most of the literature exists.

SBCE

PillCam SB1 video capsule endoscope (CE), the original CE is wireless (11 mm × 26 mm) with its light source, lens, CMOS imager, a battery and a wireless transmitter. The capsule, easily ingested, moves from the mouth to the anus via the bowels peristaltic waves (M2A-was how it was originally called). PillCam SB1’s battery provided 8 hours of work at the rate of two images per second. The capsule’s angle of view was 140 degree and it had an 8:1 magnification. The second generation (PillCam SB2) is in the market a few years now. It has a broader angle of view, 156 degrees, better optics with ALC (automatic light control), altogether allowing much better small bowel mucosal coverage. The 3rd generation-PillCam SB3 released about 1 year ago, has an adaptive frame rate allowing it to transmit up to six frames per second according to its speed of movement and has even better optics. The new “no attachments” sensor belt, delivers the pictures to a small recorder. Most of the new generation capsules in the market provide about 12 hours or more of battery time, thus allowing full view of the small bowel in practically all patients. Upon completion of the study, downloading into a Reporting and Processing of Images and Data computer workstation (RAPID 9) is done, and the examination seen as a continuous film. Many supporting gadgets were developed and added in the past 15 years. Some examples are the localization system, blood detecting monitor, the ability to see simultaneously a double or quadric picture, the quick viewer mode, or the single picture adjustment mode. Other modalities included incorporation of the Fuji Intelligent Color Enhancement (FICE) system, the inflammation (Lewis) scoring system and an atlas.

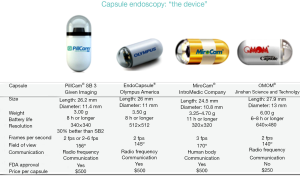

Additional small bowel capsule systems have been developed and approved for use: the Olympus EndoCapsule (Olympus, Japan), found to be as good the old generation PillCam SB1 (2), the Chinese OMOM pill (Jinshan science & technology, Chongqing, China) (3), and the Korean Miro pill (4) (Figure 1). Now a day, most of the systems in the market have different color enhancement features in their software.

Colonic CE

PillCam Colon2, the 2nd generation colonic capsule (Medtronic, USA) is available now for a few years all over the world. It is slightly larger (11 mm × 31 mm), has two cameras, and a wider 172 degrees angle of view. It also has the ability to adjust its frame rate between 2–35 frames per second from each head, based on the capsule’s speed of movement. The capsule’s battery allows >11 hours of transmission, and the new data recorder (DR3) allows the crosstalk that permits the different rates of transmission. The LCD panel on the recorder allows a real time view as well as the ability to transmit messages/instructions to the patient, depending on the capsule’s advancement. Important tools—polyp size estimator and the use of the FICE technique have also been added to the new software.

The preparation for the procedure takes into account (I) bowel cleanliness; (II) completion of the study within 11 hours (battery time). Similar preparation to that of optical colonoscopy is used up to the capsule’s swallow. This includes a clear liquid diet the day prior to the procedure. On that evening, 2 liters of PEG solution are given, and repeated early morning, of the day of the procedure. The capsule is ingested an hour later. Later on, when the capsule enters the small intestine, either Sodium Phosphate (30 mL) boost, or a sachet of PicoLax followed by a liter of water is given, in order to move it to the colon and allow its exit through while photographing. Another smaller (15 mL) boost, or sachet of PicoLax might be needed depending on the capsule’s location (5,6). Currently the percentage of capsules that are excreted while photographing from the anus exceeds 90%.

Current & future Indications for use wireless capsule endoscopy

SBCE-current

- Occult gastrointestinal bleeding-the most commonly used;

- Suspected Crohn’s disease—second most common;

- Suspected small bowel tumor;

- Surveillance of inherited polyposis syndromes—rare indication;

- Partially responsive celiac disease—quite rarely used.

All these indications have been looked at quite intensively over the past 15 years. The two that are in daily practice and are reimbursed in many countries are obscure GI bleeding and suspected Crohn’s (7-14).

Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE)-current

- Incomplete colonoscopy—most commonly used;

- Patients unwilling to undergo regular colonoscopy—second most common;

- Individuals unwilling to undergo regular colonoscopy.

There have been two multicenter studies comparing, head to head, 2nd generation CCE to optical colonoscopy, latter being the “gold standard” (5,6), and also one big study comparing both modalities in average risk surveillance population (15). A few studies comparing it to virtual colonoscopy in patients with incomplete colonoscopy were published with good results (16,17).

Future indications

Monitoring drug effects or side effects

CE can and has been used to evaluate drug induced damage on small bowel mucosa. SBCE can nicely demonstrate mucosal damage induced by either COX1 or COX2 antagonists in the small bowel. Characteristically, one may find erythema, erosions, minute ulcerations and classically web like strictures can be seen (18). Likewise, SBCE can monitor the effectiveness of drugs to protect against small bowel NSAIDS injury (19), to evaluate the mucosa of transplant patients, and in graft versus host disease (GVHD) (20,21).

Established Crohn’s disease

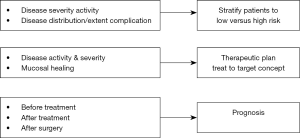

Though recent guidelines are not enthusiastic regarding the use of CE in established Crohn’s disease, there are more and more recent data showing its benefit in a few respects in this situation (Figure 2).

The use of SBCE in established CD patients has added new insights on disease phenotype (proximal distribution, stricturing disease), on disease activity in spite of normal inflammatory markers, and on data on small bowel mucosal healing and deep remission, as well as prediction of relapse (22-24).

A new video capsule—PillCam IBD has just been released to the market in Europe aimed to serve patients with suspected or known Crohn’s disease. Similar in size and configuration to the colon capsule, this is a true mouth to anus capsule that starts photographing once swallowed throughout the small and large bowel until excreted through the anus. The small bowel is divided to three parts according to length and the large bowel into two. The capsule is read looking at both cameras simultaneously in a relatively high speed and has a IBD programmed software in which one reports the most common lesion, the most severe one and the extent of disease in each of the parts giving a good clear estimation of the distribution and severity of the disease all over the gut and this is also exposed graphically. Feasibility study of this capsule without the new software has found it to be as good as ileocolonoscopy in patients with established Crohn’s (25). With the use of the patency capsule, the safety of giving a regular small bowel or even PillCam IBD capsule to patients with known Crohn’s has improved tremendously with practically no retentions. Thus, I foresee a change in the guidelines with more freedom of use of this important tool to monitor disease activity in response to different treatments.

Motility

Computer vision and machine-learning techniques allow reliable, non-invasive and automated diagnostic test of intestinal motor disorders using endoluminal image analysis (26). Unfortunately, this field has not been given enough attention and has not reached a step of routine use yet. The Smart-Pill—a “physiological” pill, has also been developed. Similar in length and diameter to the regular SBCE, the pill has pH, temperature and pressure sensors, but does not photograph. It was approved for gastric transit evaluation and characterization of constipation by the FDA.

What more can we look for? When I tried to anticipate this in 2011 I’ve created Table 1. So, let’s see what was accomplished?

Full table

Home procedure

The system is ready for use at home. This is true for SBCE, CCE as for PillCam IBD. A package (“Kit”) containing the capsule, the sensors and data recorder, with simple instructions will allow the patient to actually perform the entire test at home, possibly on a weekend, without losing working days. The DR3 recorder with its LCD updates and guides the patient on each move of the capsule, giving actual instructions on boosts as needed. Wi-Fi may allow on demand, on-line visualization.

Preparation

In this respect, we have made no progress and to my mind even regressed. Instead of 12 hours fast for the small bowel procedure, many are giving some kind of bowel preparation prior to this procedure making it much less friendly with possibly a slight increase in the diagnostic yield. There’s no doubt that cleansing is needed for a procedure involving the colon.

The preparation should be friendly, preferably using pills and not the large volume liquid solutions that are currently in use. For the colonic procedure, pill cleansers that are enteric coated, and start their effect in distal small bowel, should be the basic cleansing materials. Safer materials than the available ones, that will help propel the capsule faster to the colon should be developed.

Whole gut visualization

Just as the original capsule inventors dreamt, CE allows a comprehensive friendly examination and diagnosis of pathologies of the entire gut using a minimally invasive procedure. The new PillCam IBD complies with this dream. It starts photographing in the mouth and in >90% of patients is expelled while photographing from the anus giving excellent visualization of the whole gut. In the future external maneuvering to control capsule movement can be used. Such a pill would be a perfect tool to evaluate patients with iron deficiency anemia or suspected IBD where the pathology can be in either small or large bowel or in both.

Short video reading time

CCE video reading time is way too long—>60 minutes. This should definitely be shortened significantly, possibly by using automated detection that alerts the interpreter of existing pathologies of any sort (i.e., “pathology detector”). This will lead to a shorter CCE procedure, possibly allowing continuation with optical colonoscopy if needed. The new specific software designed for IBD in the Rapid 9 of the PillCam IBD allows the reading time of the whole gut to be much shorter.

Technological improvements

External maneuvering of capsule

A proactive capsule that treats requires either external or internal maneuvering device that will propel it to its destination. Paul Swain, reported the 1st study where a CCE (Given Imaging) was transformed to contain neodymium-iron-boron magnets in one dome, there by manipulated by an externally held magnet (“joy stick”), for a few minutes in the upper GI (27,28). Olympus and Siemens have introduced a similar concept to the Japanese pill as well (29,30). Recently a big study (>300 patients) comparing the diagnostic yield in the stomach, of a new Chinese magnetic capsule was compared to optical gastroscopy with similar results (31). Another way of doing it is to add paddles or propellers to the pill, which will start operating upon demand at various parts of the digestive tract. Finally, one can combine both mentioned above techniques—a magnet for the upper tract and an internal device for the rest of the bowel. Such a device has been tested in pigs by an Italian group. It’s easy to foresee the very thorough examination of the entire bowel done with such a device.

If these dreams come true by 2020, I think we’ll have a great minimally invasive diagnostic tool for the entire gut.

Then, we can put all our energy on a therapeutic capsule, but that’s a subject to another article.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsuleendoscopy. Nature 2000;405:417. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cave DR, Fleischer DE, Leighton JA, et al. A multicenter randomized comparison of the Endocapsule and the Pillcam SB. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;68:487-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liao Z, Gao R, Li F, et al. Fields of application, diagnostic yield and findings of OMOM capsule endoscopy in 2400 Chinese patients. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:2669-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bang S, Park JY, Jeong S, et al. First clinical trial of the "Miro" capsule endoscope by using a novel transmission technology: electric field propagation. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:253-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eliakim R, Yassin K, Niv Y, et al. Prospective multicenter performance evaluation of the second-generation colon capsule compared with colonoscopy. Endoscopy 2009;41:1026-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spada C, Hassan C, Munoz-Navas M, et al. Second-generation colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:581-589.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lewis BS, Swain P. Capsule endoscopy in the evaluation of patients with suspected small bowel bleeding: Results of a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;56:349-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, et al. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other modalities in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:2407-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, et al. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology 2004;126:643-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pasha SF, Leighton JA, Das A, et al. Double-Balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy have comparable diagnostic yield in small bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6:671-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Macdonald J, Porter V, McNamara D. Negative capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding predicts low rebleeding rates. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;68:1122-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eliakim R, Suissa A, Yassin K, et al. Wireless capsule video endoscopy compared to barium follow-through and computerized tomography scan in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis 2004;36:519-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dionisio PM, Gurudu SR, Leighton JA, et al. Capsule endoscopy has a significantly higher diagnostic yield in patients with suspected and established small-bowel Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:1240-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Annese V, Daperno M, Rutter MD, et al. European evidence based consensus for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:982-1018. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rex DK, Adler SN, Aisenberg J, et al. Accuracy of capsule colonoscopy in detecting colorectal polyps in a screening population. Gastroenterology 2015;148:948-957.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spada C, Hassan C, Barbaro B, et al. Colon capsule versus CT colonography in patients with incomplete colonoscopy: a prospective, comparative trial. Gut 2015;64:272-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rondonotti E, Borghi C, Mandelli G, et al. Accuracy of capsule colonoscopy and computed tomographic colonography in individuals with positive results from the fecal occult blood test. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1303-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Graham DY, Opekun AR, Willingham FF, et al. Visible small intestinal mucosal injury in chronic NSAID users. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:55-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujimori S, Seo T, Gudis K, et al. Prevention of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced intestinal injury by prostaglandin: a pilot randomized controlled trial evaluated by capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:1339-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neumann S, Schoppmeyer K, Lange T, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy for diagnosis of acute intestinal graft-versus-host disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:403-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yakoub-Agha I, Maunoury V, Wacrenier A, et al. Impact of small bowel exploration using video-capsule endoscopy in the management of acute graft versus host disease. Transplantation 2004;78:1697-701. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greener T, Klang E, Yablecovitch D, et al. The Impact of Magnetic Resonance Enterography and Capsule Endoscopy on the Re-classification of Disease in Patients with Known Crohn’s Disease: A Prospective Israeli IBD Research Nucleus (IIRN) Study. J Crohns Colitis 2016;10:525-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- kopylov U, Yablecovitch D, Lahat A, et al. Detection of small bowel mucosal healing and deep remission in patients with known small bowel Crohn’s disease using biomarkers, capsule endoscopy and imaging. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1316-23.

- Hall B, Holleran G, Chin JL, et al. A prospective 52 week mucosal healing assessment of small bowel Crohn’s disease as detected by capsule endoscopy. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:1601-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leighton JA, Helper DJ, Gralnek IM, et al. Comparing diagnostic yield of a novel pan-enteric video capsule endoscope with ileocolonoscopy in patients with active Crohn’s disease: a feasibility study. Gastrointest Endosc 2017;85:196-205.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malagelada C, De Iorio F, Azpiroz F, et al. New insight into intestinal motor function via noninvasive endoluminal image analysis. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1155-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swain P, Toor A, Volke F, et al. Remote magnetic manipulation of a wireless capsule endoscope in the esophagus and stomach of humans. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:1290-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keller J, Fibbe C, Volke F, et al. Remote magnetic control of a wireless endoscope in the esophagus is safe and feasible: results of a randomized, clinical trial in healthy volunteers. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72:941-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rey JF, Ogata H, Hosoe N, et al. Feasibility of stomach exploration with a guided capsule endoscope. Endoscopy 2010;42:541-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Denzer UW, Rosch T, Hoytat B, et al. Magnetically guided capsule versus conventional gastroscopy for upper abdominal complaints-a prospective blinded study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015;49:101-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liao Z, Hou X, Sheng JQ, et al. Accuracy of magnetically controlled capsule endoscopy, compared with conventional gastroscopy, in detection of gastric diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1266-73.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]