Re-assessing the role of non-fasting lipids; a change in perspective

Introduction

Lipid testing plays a major role in cardiovascular risk stratification and management in clinical practice. Despite the fact that we spend the vast majority of our time in a non-fasting state, fasting samples have long been the standard for measurement of triglycerides and cholesterol, as fasting is believed to reduce variability and allow for a more accurate derivation of the commonly used Friedewald-calculated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Another reason for preferring fasting lipid profiles has been the concern for an increase in triglyceride concentration seen after consuming a fatty meal (i.e., a fat tolerance test). However, the increase in plasma triglycerides observed after habitual food intake is much less than that observed during a fat tolerance test, making this concern less of a concern. In addition, recent studies suggest that postprandial effects do not weaken, and may even strengthen, the risk associations of lipids with cardiovascular disease (CVD). If postprandial effects do not substantially alter lipid levels or their association with cardiovascular risk, then a non-fasting blood draw has many practical and possibly economic advantages (1).

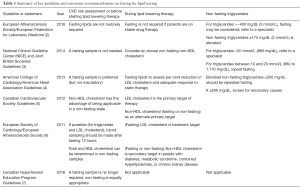

Specific attention should also be directed to the fact that in certain patients, such as diabetics, fasting may mask abnormalities in triglyceride-rich lipid metabolism, which may be pivotal in identifying those with continued residual risk despite statin treatment. Recently the joint consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society and European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine suggest that non-fasting lipids become the new standard for lipid measurement, with fasting levels obtained only in specific situations (Table 1).

Full table

Effects of the postprandial state on lipid levels and risk assessment

The major concern of clinicians regarding non-fasting lipid measurements is the variable effect of the postprandial state on lipid levels. There are, however, several studies to date that have shown that most lipid levels differ minimally after a meal compared with fasting. Clinically insignificant changes are seen; negligible changes for high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol; slight changes (up to 8 mg/dL) for total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and non-HDL cholesterol; and modest changes (up to 25 mg/dL) for triglycerides (2). In addition, CVD risk from numerous large prospective studies, over the past several decades have consistently found that non-fasting lipids are sufficient for general screening of cardiovascular risk (8-10). Both clinical events (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke, and coronary revascularization) and mortality have been assessed in these studies, finding consistent associations for non-fasting lipids with CVD. Those studies that have included both fasting and non-fasting groups of patients have shown either similar, at times even greater, CVD risk associations for non-fasting lipids (including for LDL cholesterol and triglycerides) compared with fasting lipids.

In addition, a meta-analysis from 68 prospective studies, 20 of which used non-fasting blood samples, found no attenuation of lipid relationships with predicting incident events (N=103,354; number of events 3,829) for non-fasting lipids (10). Finally, at least three large statin clinical trials have used non-fasting lipids (involving nearly 43,000 patients) (10). The overall evidence from these findings suggests that measuring non-fasting lipids confers no disadvantage with respect to risk assessment, and in certain instances may be preferred.

Safety and economic benefits

While there are no studies to date specifically assessing the cost-effectiveness of fasting versus non-fasting lipid testing, it is not difficult to surmise that non-fasting lipids would be more economical and safer for certain groups of patients, such as diabetics. In fact, according to a pilot study by Aldasouqi et al. (11) up to 27.1% of diabetic patients experience a fasting-evoked en-route hypoglycemic event due to fasting for blood tests. These events are vastly under reported and add considerably to patient morbidity, suggesting that a shift in practice is mandated for these patients.

It is also important to note, as is mentioned in the EAS and EFMS joint committee recommendations, that obtaining a non-fasting screening test in no way precludes the use of a second fasting test if clinically indicated. In the Danish experience (where a non-fasting lipid profile has been the standard since 2009) (2), only 10% of patients who underwent non-fasting lipid profiles needed repeat laboratory testing for a fasting panel.

As is well known, improvements in quality and efficiency result in decreased healthcare expenditures. In terms of fasting lipids, many patients are not fasting on initial evaluation by their providers resulting in a repeat visit if a lipid profile is indicated. Patients are often required to expend additional resources to return to a laboratory for fasting levels and some may forgo coming back altogether. If patients return for their doctors’ appointment without testing, this resultant follow up visit is one where key laboratory data is not available and often management decisions are deferred. These visits consume additional health care dollars and resources, and also potentially deprive other patients from access to needed care, as well as adding to length of patient waiting times.

Coupled to patient inconvenience, healthcare practitioners who send patients for fasting blood work on an alternate day, bear the responsibility of ensuring these tests occur, which adds additional burden on already overwhelmed practitioners and generates system wide inefficiencies. From a laboratory perspective, requiring routine fasting lipid samples may also reduce laboratory workflow efficiency due to the early morning congestion of visits for lipid testing. All of these factors would contribute to lack of efficiency and quality in the health care system and consequently to increased health care costs.

Guidelines and recommendations

It is with all of these findings in mind, that recommendations for the clinical use of non-fasting lipids have become more widespread. The evolution of recommendations of different expert panels and societies is summarized in Table 1 and highlights the growing evidence base for non-fasting lipid testing. It is not a new finding that practice guidelines allow for the measurement of non-fasting total and HDL cholesterol (and hence the calculated values from these: non-HDL cholesterol and the total/HDL cholesterol ratio) (12), since levels of these lipids are essentially unaltered when measured in fasting or non-fasting specimens. In the U.S., the third report of the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III, 2001) (12) the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines (4) both recommended that initial screening should include a fasting lipid profile, although they allowed for measuring non-fasting total, HDL, and non-HDL cholesterol (12).

However over the past few years, a shift in practice recommendations has occurred. The National Clinical Guideline Center (NICE) and Joint British Societies recommended in 2014, that a fasting sample is not needed for routine clinical care (3). Most recently, in 2016, the European Atherosclerosis Society and the European Federation of Laboratory Medicine recommended using non-fasting lipid testing for routine clinical practice and provided specific cut-points for desirable fasting and non-fasting lipid levels (2). Elevated non-fasting triglycerides were defined as ≥175 mg/dL (≥2 mmol/L) (2,13), and repeat measurement of fasting triglycerides were suggested when non-fasting levels are greater than ~400 mg/dL (2). In a change from their previous recommendations, the 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program guidelines have now removed fasting as a requirement from lipid testing. This major shift in newer guidelines reflects the changing focus of risk assessment from LDL to non-HDL cholesterol (apolipoprotein B) as a better predictor of risk.

Limitations of evidence

Currently there are no studies assessing the predictive value of lipids measured both fasting and non-fasting from the same individuals, and no randomized outcomes trials or cost-effectiveness analyses. More data is also needed assessing individuals from different ethnic backgrounds.

Conclusions

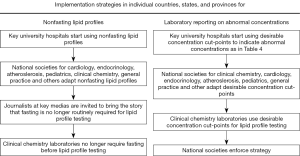

In summary, robust evidence supports the use of non-fasting blood draws for routine clinical practice and widespread adoption would be favorable for both patients and healthcare providers. The fasting panel now has a much more limited role, predominantly in the setting of abnormally high triglycerides and prior to starting treatment in patients with genetic lipid disorders. For the majority of patients though, the non-fasting test is safe, convenient and reflects an improvement in health care delivery. Methods to bring this testing strategy into mainstream clinical practice have been suggested by the EAS and EFLM consensus statement shown in Figure 1 (1). The sooner this occurs, the sooner the benefits of efficient health care will be realized for patients and practitioners alike.

Acknowledgements

Funding: Dr. Farukhi was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (T32 HL007575).

Footnote

Provenance: This is a Guest Editorial commissioned by Executive Editor Zhi-De Hu (Department of Laboratory Medicine, General Hospital of Ji’nan Military Region, Ji’nan, China).

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Mora has served as a scientific consultant (modest) to Lilly, Pfizer, Quest Diagnostics, Amgen, and Cerenis Therapeutics. Dr. Mora has received institutional research grant support from the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01HL117861) and from Atherotech Diagnostics. The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Rifai N, Young IS, Nordestgaard BG, et al. Nonfasting Sample for the Determination of Routine Lipid Profile: Is It an Idea Whose Time Has Come? Clin Chem 2016;62:428-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A, Mora S, et al. Fasting is not routinely required for determination of a lipid profile: clinical and laboratory implications including flagging at desirable concentration cut-points-a joint consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society and European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1944-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Lipid Modification: Cardiovascular Risk Assessment and the Modification of Blood Lipids for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2014.

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129:S1-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anderson TJ, Grégoire J, Hegele RA, et al. 2012 update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol 2013;29:151-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation, Reiner Z, Catapano AL, et al. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J 2011;32:1769-818. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al. Hypertension Canada's 2016 Canadian Hypertension Education Program Guidelines for Blood Pressure Measurement, Diagnosis, Assessment of Risk, Prevention, and Treatment of Hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:569-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mora S, Rifai N, Buring JE, et al. Fasting compared with nonfasting lipids and apolipoproteins for predicting incident cardiovascular events. Circulation 2008;118:993-1001. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Langsted A, Freiberg JJ, Nordestgaard BG. Fasting and nonfasting lipid levels: influence of normal food intake on lipids, lipoproteins, apolipoproteins, and cardiovascular risk prediction. Circulation 2008;118:2047-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, et al. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA 2009;302:1993-2000. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aldasouqi S, Corser W, Abela G, Mora S, Shahar K, Krishnan P, Bhatti F, Hsu A, Gruenbaum D. Fasting for lipid profiles poses a high risk of hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes: A pilot prevalence study in clinical practice. International Journal of Clinical Medicine. In Press.

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002;106:3143-421. [PubMed]

- White KT, Moorthy MV, Akinkuolie AO, et al. Identifying an Optimal Cutpoint for the Diagnosis of Hypertriglyceridemia in the Nonfasting State. Clin Chem 2015;61:1156-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]