Mitral valve replacement in a dialysis-dependent patient

Introduction

Patients with end-stage renal disease have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality following cardiac surgery. Cardiac, pulmonary, metabolic, and hematological complications have a major effect on outcome after cardiac surgery. However, end-stage renal disease should not be regarded as an absolute contraindication to open heart surgery. Valve replacement in patients with end-stage renal disease has been previously reported (1-4). However, there is limited experience in these patients. We report a case of successful mitral valve replacement (MVR) in a dialysis-dependent patient.

Case presentation

Patient

A 52-year-old man with a history of 15 years of hypertension had hemorrhagic stroke and renal failure in 2009. The patient then accepted peritoneal dialysis after arteriovenous graft thrombosis. Perioperative variables of the patient are shown in Table 1. On October 15, 2014, the patient underwent MVR because of severe mitral insufficiency due to tendon rupture of posterior leaflet. After surgery, systemic antibiotics (cefotiam, q12h) (Fontiam; Hanmi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Siheung, Korea) were injected for 14 days until body temperature and the white blood cell count reached normal levels. A dosage of 2–7 µg/kg/min dopamine was continuously injected for 19 days. Nutritional support was provided orally and intravenously for 20 days, and anticoagulation therapy with warfarin was started on October 16 (targeting of the international normalized ratio was 1.8–2.2).

Full table

Hemodialysis

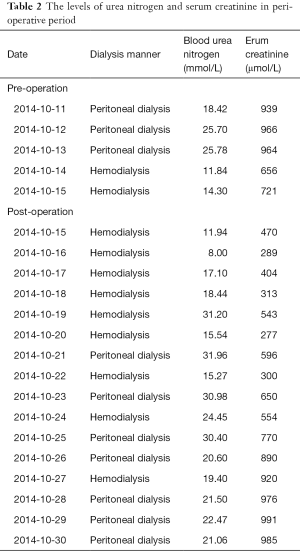

The patient underwent hemodialysis on the day before the operation and began hemodialysis again 4 hours after surgery via a catheter in the right femoral vein. Heparin was selected as the anticoagulant agent for hemodialysis and the activated coagulation time was used to monitor heparinization. Levels of serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen were controlled at 674.95±262.27 µmol/L (277–991 µmol/L) and 20.78±6.87 mmol/L (8–31 mmol/L), respectively. Levels of serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen on every day of the perioperative period are shown in Table 2.

Full table

MVR

The procedures were performed through a median sternotomy. Cardiopulmonary bypass was established between the ascending aorta and both venae cavae. Myocardial protection was achieved using high-potassium cold blood cardioplegia in an antegrade fashion. MVR was performed using a mechanical prosthesis (MVR; 27-mm size mechanical Sorin valve) with interrupted mattress sutures via the transseptal approach. After de-airing, the patient was weaned off cardiopulmonary bypass with a moderate dose of inotropic medication.

The cardiopulmonary bypass time was 77 minutes and the time of cross-clamping was 43 minutes. After surgery, 4 U concentrated red blood cells, 400 mL plasma, 90 g human serum albumin, and 6 g immunoglobulin were transfused. The patient recovered well at post-operation with no complications, such as low cardiac output syndrome, hypoxia, hyperkalemia, fluid overload, and cerebrovascular accidents.

Follow-up

The patient was discharged 33 days after surgery and had good left ventricular function. At 25 months of follow-up, the patient had gingival bleeding once (prothrombin time was 32.3 s and the international normalized ratio was 3.2) and pulmonary hemorrhage once (Figure 1) (prothrombin time was 33.5 s and international normalized ratio was 3.36). In these emergency situations, the effect of warfarin was reversed by injection of vitamin K1.

Discussion

With an increasing population of patients in end-stage renal failure, more patients on chronic dialysis will require open heart surgery. Patients with end-stage renal disease have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality following cardiac surgery. However, end-stage renal disease should not be regarded as an absolute contraindication to open heart operation. Success of cardiac surgery in patients with end-stage renal disease depends on management of hypertension, electrolytic disturbance, metabolic acidosis, anemia, myocardial protection, bleeding, malnutrition, and glucose intolerance. Based on our successful case, we consider that there are several issues that should be of concern in valve replacement for patients with end-stage renal disease.

The first issue is that peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis require normal arterial blood pressure. Therefore, maintaining normal arterial blood pressure is important after an operation. However, myocardial protection plays a specific role in maintaining postoperative normal arterial blood pressure. Therefore, myocardial protection becomes more notable in procedures of valve replacement for patients with preoperative myocardial dysfunction and end-stage renal disease. Among the various myocardial protection strategies, high-potassium cold blood cardioplegia is the most wildly accepted strategy. Therefore, high-potassium cold blood cardioplegia was used as a method of myocardial protection in our patient. Our patient chose valve replacement, instead of valve repair, because there was an increased risk of reoperation (MVR) in valve repair and an increased risk of prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass time if valve repair failed. He feared having a reoperation and was concerned about the medical cost of a reoperation. For better myocardial protection, some dialysis-dependent patients undergo valve replacement in an empty-beating heart (5).

Second, the aim of hemodialysis is to maintain stability of the internal environment and normal function of organs. However, care must be taken in using anticoagulants in hemodialysis. Our patient required peritoneal dialysis after arteriovenous graft thrombosis. However, hemodialysis was necessary in this patient for greater stability of the internal environment during the perioperative period. During hemodialysis, administration of an anticoagulant agent depends on blood coagulation function. In our patient, when satisfactory anticoagulation efficacy had been achieved for a mechanical prosthesis, no anticoagulant agent was used in hemodialysis.

Third, patients with end-stage renal disease show an immune defect characterized by an increased susceptibility for infections and a decreased immune response (6,7). Therefore, end-stage renal disease is associated with a higher risk for infectious complications. The mechanisms underlying the impaired immune response in dialysis-dependent patients are not completely understood. Care must be taken to prevent postoperative infection. Dialysis, malnutrition, and compromised immunity are associated with infection. In addition, catheters are associated with stronger risks of infection. In our patient, systemic antibiotics, transfusion of immunoglobulin, and nutritional support were used to prevent infection.

Fourth, nutritional support should be emphasized in dialysis-dependent patients with valvular disease because poor appetite and anemia are usually present, and these can result in malnutrition. There is an association between malnutrition and increased morbidity and mortality. Well-nourished patients appear to respond most favorably to treatment because nutritional support can improve cellular immune function (8). In our patient, nutritional support was provided orally and intravenously for 20 days.

The final issue is that hemorrhage is a common complication in patients with end-stage renal disease using antithrombotic agents (3,9). The risk of anticoagulant-induced hemorrhage may be reduced by close monitoring. Dialysis-dependent patients are at a higher risk of serious bleeding due to several factors, including uremic platelet dysfunction, anemia, and heparin use during dialysis (10-13). Current guidelines for immediate reversal of anticoagulation recommend administration of vitamin K1 and factor replacement with either factor concentrates or fresh frozen plasma. Our patient had bleeding twice during anticoagulation. There may be two reasons for this finding as follows: there was impairment of the coagulation system and the international normalized ratio proposed for Chinese is 1.8–2.2 (14-17). In our patient, we used vitamin K1 for reversal of anticoagulation. Tissue valves are recommended to eliminate anticoagulant-induced hemorrhage (18-22). However, considering that tissue valves are more susceptible to early calcification and degeneration (3,5) and the fact that our patient was only 52 years old, a bioprosthesis was inappropriate for our patient.

Conclusions

Myocardial protection, prevention of infection, nutritional support, and close monitoring of blood coagulation function are important in dialysis-dependent patients undergoing valve replacement.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

References

- Li XH, Li Y, Xiao F, et al. Peri-operative management and follow-up outcomes of cardiac surgery in dialysis-dependent patients with end stage renal disease. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao 2013;45:634-8. [PubMed]

- D'Alessandro DA, Skripochnik E, Neragi-Miandoab S. The significance of prosthesis type on survival following valve replacement in dialysis patients. J Heart Valve Dis 2013;22:743-50. [PubMed]

- Nakatsu T, Tamura N, Yanagi S, et al. Hemorrhage as a life-threatening complication after valve replacement in end-stage renal disease patients. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;63:386-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Najjar M, Yerebakan H, Sorabella RA, et al. Reversibility of chronic kidney disease and outcomes following aortic valve replacement†. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2015;21:499-505. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horst M, Easo J, Hölzl PP, et al. Beating heart valve surgery using stentless xenografts as a surgical alternative for patients with end-stage renal failure. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;56:428-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nucifora G, Badano LP, Viale P, et al. Infective endocarditis in chronic haemodialysis patients: an increasing clinical challenge. Eur Heart J 2007;28:2307-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kitamura T, Edwards J, Khurana S, et al. Mitral paravalvular abscess with left ventriculo-atrial fistula in a patient on dialysis. J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;4:35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ash S, Campbell KL, Bogard J, et al. Nutrition prescription to achieve positive outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Nutrients 2014;6:416-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sood MM, Larkina M, Thumma JR, et al. Major bleeding events and risk stratification of antithrombotic agents in hemodialysis: results from the DOPPS. Kidney Int 2013;84:600-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaw D, Malhotra D. Platelet dysfunction and end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial 2006;19:317-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gangji AS, Sohal AS, Treleaven D, et al. Bleeding in patients with renal insufficiency: a practical guide to clinical management. Thromb Res 2006;118:423-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holden RM, Harman GJ, Wang M, et al. Major bleeding in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;3:105-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Limdi NA, Beasley TM, Baird MF, et al. Kidney function influences warfarin responsiveness and hemorrhagic complications. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:912-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haibo Z, Jinzhong L, Yan L, et al. Low-intensity international normalized ratio (INR) oral anticoagulant therapy in Chinese patients with mechanical heart valve prostheses. Cell Biochem Biophys 2012;62:147-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- You JH, Chan FW, Wong RS, et al. Is INR between 2.0 and 3.0 the optimal level for Chinese patients on warfarin therapy for moderate-intensity anticoagulation? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005;59:582-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu Z, Ding YL, Lu F, et al. Warfarin dosage adjustment strategy in Chinese population. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:9904-10. [PubMed]

- Li S, Zou Y, Wang X, et al. Warfarin dosage response related pharmacogenetics in Chinese population. PLoS One 2015;10:e0116463. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brinkman WT, Williams WH, Guyton RA, et al. Valve replacement in patients on chronic renal dialysis: implications for valve prosthesis selection. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:37-42; discussion 42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaplon RJ, Cosgrove DM 3rd, Gillinov AM, et al. Cardiac valve replacement in patients on dialysis: influence of prosthesis on survival. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;70:438-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan V, Jamieson WR, Fleisher AG, et al. Valve replacement surgery in end-stage renal failure: mechanical prostheses versus bioprostheses. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;81:857-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thourani VH, Sarin EL, Keeling WB, et al. Long-term survival for patients with preoperative renal failure undergoing bioprosthetic or mechanical valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:1127-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan V, Chen L, Mesana L, et al. Heart valve prosthesis selection in patients with end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 2011;97:2033-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]